A forgotten fossil stashed away in an Italian museum has given scientists a new appreciation for just how big a predatory, carnivorous dinosaur called abelisaur must have been.

PhD student Alessandro Chiarenza, then at the University of Bologna and now at Imperial College London, asked officials with the Museum of Geology and Palaeontology in Palermo, Italy if he could examine a fossilized femur that had previously gone unidentified.

After Chiarenza’s analysis, it turned out that the bone was from a 95-million-year-old representative of abelisauridae, a group of dinosaurs that had powerfully muscled hind limbs, razor-sharp teeth, tiny forelimbs, and probably feathers.

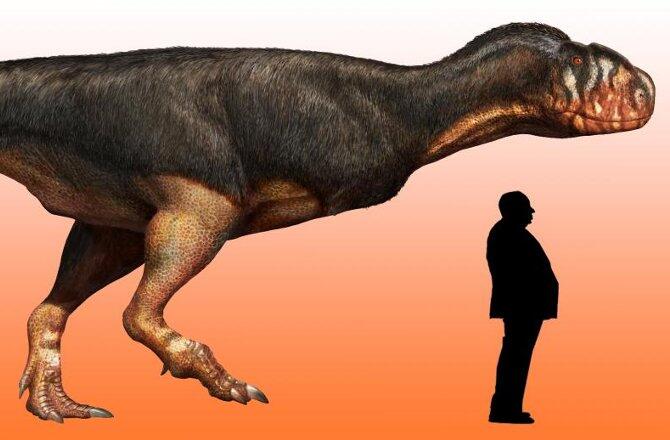

The abelisaur Chiarenza studied would have been about 29 and a half feet (9 meters) long and likely weighed 1 to 2 tons, and those numbers have given scientists a better idea of the peak size of these dinos.

“Smaller abelisaur fossils have been previously found by palaeontologists, but this find shows how truly huge these flesh-eating predators had become,” said Chiarenza, in a statement. “Their appearance may have looked a bit odd, as they were probably covered in feathers, with tiny, useless forelimbs, but make no mistake: They were fearsome killers in their time.”

The big dino lived in late-Cretaceous North Africa, a tropical world of rivers and mangrove swamps, with plenty of large fish, turtles, crocodiles and other dinosaurs to eat.

The femur came from a fossil bed in Morocco called the Kem Kem Beds, known for containing dinosaur remains from five — now six, including abelisaur — different groupings of predators.

Scientists have long puzzled over how so many predators could have coexisted in the same place without tearing each other to bits.

Chiarenza and University of Bologna colleague Andrea Cau argue that abelisaur and friends actually lived apart from each other, in different environments, and that over time the changing geology of the region mixed the fossils of the different predators together.

“Rather than sharing the same environment, which the jumbled-up fossil records may be leading us to believe,” Chiarenza said, “we think these creatures probably lived far away from one another in different types of environments.”

A study on the new findings about this hefty creature have just been published by Chiarenza and Cau in the journal Peer J.

And, as for that drawer that held the forgotten fossil? “Our study shows how museums still play an important role in preserving specimens of primary scientific value, in which sometimes the most unexpected surprises can be discovered,” Cau said. “As Stephen Gould, an influential palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist, once said, ‘sometimes the greatest discoveries are made in museum drawers’.”

Source: Discovery