Wyoming regulators downplayed health concerns, glossed over ambiguities and made unsubstantiated claims about the source of contamination in their study of the polluted drinking water east of Pavillion, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency review shows.

Those findings, delivered in comments to the state earlier this month, raised questions over state officials’ contention that natural gas operations are not responsible for pollution found in some water wells outside this central Wyoming community of roughly 230 people.

A draft study released by the state Department of Environmental Quality in December concluded hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, likely played little role in polluting water wells in the Pavillion area. It linked contamination in the those wells to naturally occurring pollutants. Methane buildup in landowners’ water was more likely a product of natural seepage from shallow geologic formations than gas production, the state concluded.

The EPA repeatedly questioned those claims in its review of the state study, saying Wyoming investigators lacked the evidence, or relied on limited proof, to make their assertions.

Federal regulators noted the DEQ did not cite any evidence for its claim that small amounts of fracking fluid were used to stimulate the Pavillion field’s gas wells — a central tenant of the state’s argument that the practice was not to blame for the polluted water.

And while state investigators acknowledged a gap in the protective layer encasing many Pavillion gas wells, they failed to examine whether fracking fluids could have escaped through those openings, the EPA found.

“In summary, the data limitations and uncertainties … suggest a need for additional investigation to provide support for many of the report’s conclusions related to fluid movement, gas source and well integrity,” the agency wrote.

EPA’s comments came in response to a DEQ report examining the water quality of 13 Pavillion-area drinking wells. The report is one of three produced by the state regarding Pavillion. The others examined well integrity and disposal pits in the area.

A DEQ spokesman said the department had no comment on EPA’s review. Wyoming will issue an official response to comments as part of its official investigative process, said Keith Guille.

“We’re not going to respond through the media,” he said.

State officials have not offered a timeline for when the report will be finalized.

Encana Corp., the Calgary-based firm that operates the Pavillion field, also declined to comment on the EPA’s findings.

The company, in its own review of the state study, called Wyoming’s investigation “a significant, rigorous effort” to better understand the Pavillion field. Encana paid $1.5 million to help finance Wyoming’s study.

Wyoming’s draft report recommends more analysis, particularly to determine how much gas is seeping up along the well bores to shallower geologic formations where water is found.

But Encana contested that recommendation, saying no further investigation is needed. Pressures found in its gas wells are not sufficient to push gas into water-bearing zones, the company said.

Poor maintenance of water wells in the area is likely responsible for many of the issues, Encana said.

Pavillion has long served as a symbol in the wider national debate over fracking — the practice of injecting water, sand and fluids at high pressure into oil and gas wells to stimulate production.

Residents began complaining to state officials about faulty water in the early 2000s. After the state declined to investigate, it turned to the EPA, which released a preliminary study in 2011 concluding the bad water was linked to fracking.

The agency never finalized its study, however. Its findings were met with fierce opposition from state officials, industry groups and Congressional Republicans. The EPA ultimately dropped the investigation in 2013, turning the inquiry over to Wyoming. A 2015 Star-Tribune investigation found federal officials were worried they could not support their conclusions in the face of sustained opposition to the study.

Public comments on the DEQ’s investigation highlight the lingering uncertainty over the cause of the Pavillion-area’s water issues.

Halliburton Energy Services Inc., a fracking provider, said it agreed with Wyoming’s analysis that fracking fluids did not contribute to Pavillion’s problems. Between 1,000 and 10,000 gallons of frack fluid were used per well interval, with 70 percent of the fluid made up of carbon dioxide foam, the company said.

Pressure gradients in the Wind River formation underlying the Pavillion field are also more likely to push fracking fluids down, not upward toward water resources, Halliburton said.

But others lambasted the study. Sue Spencer, a professional geologist from Laramie, said the state inquiry produced vague results because it only relied on water samples from domestic wells. Groundwater monitoring wells are needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the situation, she said.

“This report represents yet another thinly veiled attempt by the state of Wyoming and industry consultants to attribute the groundwater contamination in the Pavillion area to problems with private water supply wells rather than on improperly constructed gas wells and unlined surface disposal pits,” Spencer wrote.

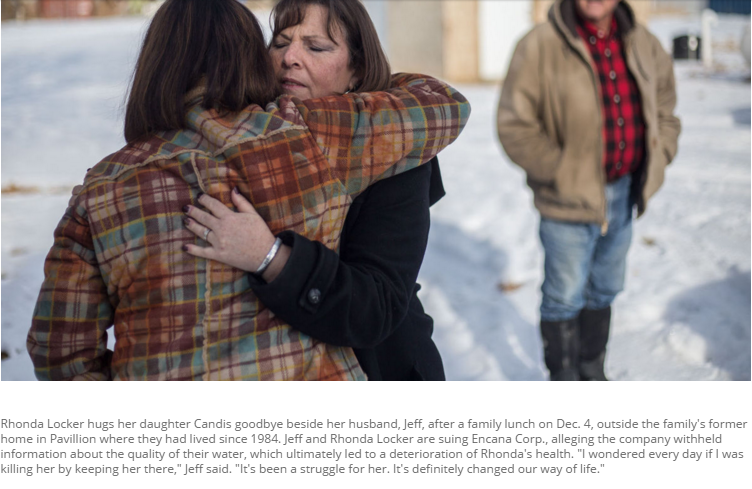

Spencer is working as an expert in a lawsuit brought by a Pavillion family who claim Encana’s operations contaminated their water.

Lisa McClain-Vanderpool, an EPA spokeswoman, said the comments were meant to provide Wyoming with technical input on its study.

“Many of our recommendations suggest that important information gaps be filled to better support conclusions drawn in the report, and that uncertainties and data gaps be discussed in the report,” she said in an email.

The agency said more evidence was needed to bolster state investigators’ contention that much of the gas found in water wells was naturally occurring.

In one instance, the DEQ cited a 1951 Bureau of Reclamation report that said a 500-foot water well was destroyed by gas. But that well was 2.5 miles away from the nearest well in the Pavillion study area, the EPA noted.

In another case, the state relied on a publicly unavailable letter from the Wyoming Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to support its claim.

“The report concludes that it is ‘almost certain’ that part of the methane observed in the water supply wells in the WDEQ investigation is naturally occurring and not a result of gas production,” EPA wrote in its comments to the state. “This conclusion appears to be based solely on the limited data described above.”

Little historical evidence exists to support the state’s argument that the pollution is naturally occurring, the agency said. A U.S. Geological Survey report identified 20 water wells out of 359 with problems in the wider Pavillion area. Those wells were contaminated by “bad water,” hydrogen sulfide or some combination of sulfur and gas, but none were located inside the study area under review.

Complicating matters further is the fact that comparison values used to gauge health risks don’t exist for nine of the 19 organic constituents identified by the state, the EPA said.

Wyoming regulators had said they found only two instances where chemicals exceeded drinking water standards. One was linked to a pesticide. The other is a common laboratory contaminant.

The state largely cast Pavillion’s water issues as a palatability concern and is suitable to use despite exceeding some safety thresholds. That characterization could leave the report’s readers unclear about the significance of safety exceedances, the EPA said, recommending some discussion of health risks be included in the report.

“Given the number of detected compounds with no (comparative value), uncertainty remains with respect to statements about health risk and suitability, and EPA suggests any such statements be qualified accordingly,” the agency wrote.

Source: Billing Gazzette