The U.S. military has launched a program to equip its front-line soldiers with the latest battlefield technology. The Squad X initiative would give an Army or Marine Corps squad new computerized weapons, the latest smartphone-style communications and even easy-to-use robot helpers.

The program aims to help the troops “have deep awareness of what’s around them, detect threats from farther away and, when necessary, engage adversaries more quickly and precisely,” according to Army Major Christopher Orlowski, who’s managing the Squad X effort on behalf of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Pentagon’s cutting-edge science department.

Squad X is still just a concept. It’ll be up to Orlowski, other DARPA officials and the defense industry to determine exactly what technology the program includes. But one thing is clear: The government wants to profoundly change the way squads move, communicate and fight.

The problem is, the military has tried these sorts of technical advances before. Several times, in fact. Not only did the previous attempts fail, they cost American taxpayers billions of dollars.

So Orlowski and the advanced research agency have their work cut out for them. Meanwhile Americans have plenty of reasons to be skeptical they’ll succeed — and not just because the Pentagon has repeatedly failed to manage complex weapons programs without cost overruns and technical problems, the prime example being the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

The Pentagon launched Squad X in 2013, to solve longtime serious problems. A squad, which is roughly a dozen troops, is the smallest conventional military unit capable of fighting independently. A “dismounted” squad — meaning traveling on foot rather than in vehicles — usually carries rifles, grenades, a few machine guns and several radios. It depends on larger units for speedy transportation, heavy firepower and long-range communications.

Today, and throughout recent history, squads have fought under major constraints. Squad members constantly struggle to keep track of each other and the enemy. They can only see what’s in their direct line of sight — and can only shoot what they can see.

“Dismounted squads lack the detailed situational awareness, robust networked communications and data-sharing capability that supports the ability to consistently anticipate the tactical situation,” the Pentagon explained in its initial Squad X announcement.

That’s why squads are easily surprised “due to their lack of real-time data about squad members, their surrounding environment and the threats present,” the Defense science agency added.

The Pentagon tried as far back as the late 1990s to solve these problems. Then, the focus was on networking — that is, connecting every soldier to every other soldier as well as to other units and even to distant planes and command posts.

The Army’s Land Warrior program, launched in 1993, tried to equip every soldier with his own high-tech radio and wearable computer, plus an eyepiece projecting an airplane-style Heads-Up Display. Every soldier would see the position of every other soldier — and the enemy — as an icon on a digital map displayed on the eyepiece.

With a glance, a soldier would fully understand how a battle was unfolding. Allied forces on the ground, in the sky and even in space would constantly add updated information to the trooper’s personal display, transmitting that data potentially thousands of miles.

At least that is what was supposed to happen.

It took the Army 15 years and a half-billion dollars to produce a few sets of the Land Warrior gear. It equipped a Washington State-based infantry unit and sent them to Iraq in 2007, to test the hardware in combat.

The infantrymen hated the gear. At 16 pounds, it was far too heavy. And its 1990s-vintage processors and software were slow by 2007 standards. “It makes you a slower, heavier target,” Sergeant James Young complained to Popular Mechanics.

The Pentagon belatedly canceled Land Warrior — sort of — in 2007. In fact, Land Warrior survived as an Army program called “Nett Warrior.” The new initiative, launched in 2010, replaced the wearable computer and eyepiece with a smartphone connected to a lightweight radio.

Strapped to a soldier’s chest, the smartphone functions as a tiny computer screen that displays a map showing the locations of other soldiers. A soldier can send text messages to his squadmates instead of shouting or speaking into the radio.

But Nett Warrior suffered some of the same problems as Land Warrior. Its map showed other soldiers in the wrong locations. It suffered unbearable lag.

Soldiers testing the gear in New Mexico in 2011 were blunt. “It ain’t ready,” one private told the trade publication Breaking Defense.

The Army is still trying to work out the kinks in Nett Warrior. Meanwhile, it has bought thousands of sets that cost millions of dollars.

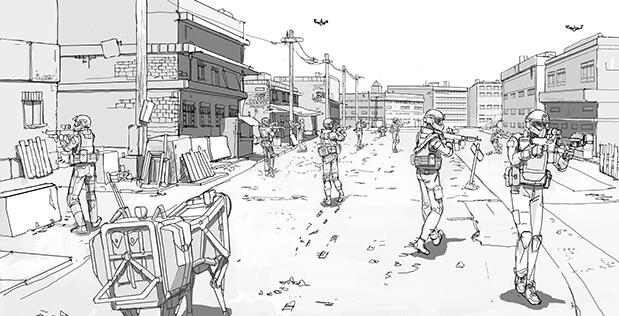

The advanced research agency hasn’t yet selected specific technologies for the Squad X program, but official concept art released with the announcement suggests what kinds of gear it hopes to include in Squad X.

The art depicts a soldier firing a tiny, precision-guided “smart” munition from his otherwise standard-looking assault rifle. It’s a striking idea — but one that could be years away from actual use in combat. The military has only recently begun to experiment with tiny, maneuverable projectiles smart enough to track a target and also small enough to be fired from, say, a rifle.

The drawings also show soldiers accompanied by a wide range of robots, including self-driving jeeps, low-flying surveillance drones, four-legged cargo robots and humanoid-looking ‘bots that appear to be scouting ahead of the soldiers. All these types of robots do exist in prototype. As with the smart munitions, however, it could be years before they’re ready for use in combat.

The captions on the artwork indicate that all the soldiers, robots and munitions constantly gather and share information, to create a kind of small-scale battlefield data network – one that constantly adapts to local conditions and might not necessarily depend on satellites or any other long-range communications, as many of today’s military networks do. These ad-hoc networks have long been a dream of Pentagon technologists.

The promotional art lends Squad X a science-fiction vibe. But that doesn’t mean the program has totally lost touch with reality. With Squad X, Orlowski and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency clearly hope to address problems that Land Warrior and Nett Warrior tried — and failed — to solve more than 20 years ago. They insist this third attempt is different from the earlier efforts.

For starters, Squad X is watching its weight. The new advanced technology “will minimize system size, weight and power,” the research agency said, “so that they are soldier-portable.” In total, it would have to weigh less than Land Warrior’s 16 pounds to please soldiers who complained about the earlier technology.

As commercial-grade phones, cameras, radios and drones get smaller and lighter by the day, it at least seems possible for the agency to outfit squads without overloading them.

The Squad X initiative is also trying to avoid the network latency, or lag, that plagued both Land Warrior and Nett Warrior. As the advanced research agency explained, “the capacity of modern sensors to generate and distribute collected data… can quickly saturate even advanced wireless radio networks.”

To prevent this, Squad X tech aims to rely on wireless devices that are “short-range, high-bandwidth … low-power, covert and resistant to electronic warfare countermeasures.”

Indeed, the research agency requires that the new hardware work even on a “GPS-denied” battlefield — where the enemy has blocked access to the navigational satellites that U.S. troops rely on.

That requirement doesn’t overestimate America’s potential enemies. When Land Warrior and Nett Warrior launched, the United States enjoyed superiority in what the military calls the “electromagnetic domain.” In other words, U.S. forces could count on their radio signals getting through unimpeded.

But in recent years Russia, China, Iran and other countries have refined technology that can jam global-positioning-system signals. U.S. forces can no longer assume that GPS will work during wartime — so Orlowski and his research agency aren’t assuming that, either, as they oversee the Squad X effort.

The science agency is counting on drones to fill in where GPS fails. Squad X aims to “increase squad members’ real-time knowledge of their own and teammates’ locations … through collaboration with embedded unmanned air and ground systems. Capabilities of interest include robust collaboration between humans and unmanned systems.”

It’s not hard to guess how that might work. If a soldier is in contact (via a strong, narrow radio signal) with at least two other soldiers or robots — even small, hand-thrown flying drones could work — then he can figure out where he is in relation to the other troops or ‘bots using a mathematical process called triangulation.

A little math and few landmarks make it possible for a small group of people and machines to locate each other and navigate without relying on distant spacecraft beaming jammable, long-range radio signals.

This close cooperation with drones is one of Squad X’s most important new features — yet it could prove the most difficult for Orlowski and the agency to master.

After all, if history has proved anything with regard to new squad tech, it’s that something — weight, communications lag or some other technical challenge — will complicate, and potentially doom, what might seem like a straightforward attempt to equip frontline fighting units with the latest gadgets.

The advanced research agency and Orlowski are obviously hoping that the third time is the charm for the U.S. military’s high-tech squad makeover. DARPA is set to host a meeting in Virginia in late April to begin enlisting private industry’s help in developing the new hardware. Only time will tell if Squad X finally manages to outfit front-line squads with new technology … that actually works.

Source: REUTERS