The planet in question, named PTFO8-8695 b, was identified as a candidate exoplanet in 2012 by the Palomar Transit Factory’s Orion survey.

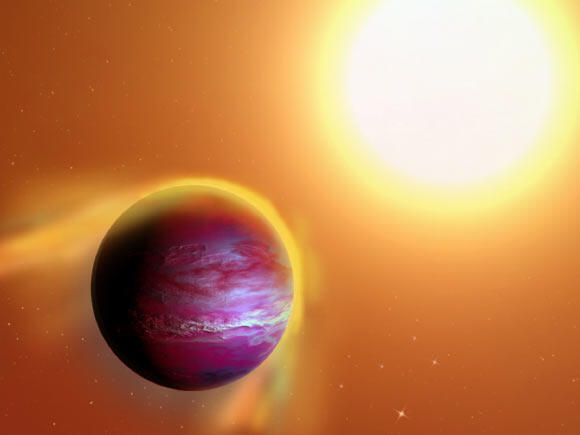

It is at most twice the mass of Jupiter and is located very close to its host star, the 2 to 3 million-year-old T Tauri star PTFO8-8695, orbiting once every 11 hours.

This young planetary system lies approximately 1,100 light-years from Earth in the constellation Orion.

“We don’t know the ultimate fate of this planet. It likely formed farther away from the star and has migrated in to a point where it’s being destroyed,” said Dr. Christopher Johns-Krull, an astronomer at Rice University.

“We know there are close-orbiting planets around middle-aged stars that are presumably in stable orbits.”

“What we don’t know is how quickly this young planet is going to lose its mass and whether it will lose too much to survive.”

The orbit of PTFO8-8695 b sometimes causes it to pass between its star and our line of sight from Earth, therefore astronomers can use a technique known as the transit method to determine both the presence and approximate radius of the planet based on how much the star dims when the planet ‘transits,’ or passes in front of the star.

“In 2012, there was no solid evidence for planets around 2 million-year-old stars,” said Dr. Lisa Prato of Lowell Observatory.

“Light curves and variations of this star presented an intriguing technique to confirm or refute such a planet.”

A spectroscopic analysis of the light coming from PTFO8-8695 revealed excess emission in the H-alpha spectral line, a type of light emitted from highly energized hydrogen atoms.

Dr. Johns-Krull, Dr. Prato and their colleagues found that the H-alpha light is emitted in two components, one that matches the very small motion of the star and another than seems to orbit it.

“We saw one component of the hydrogen emission start on one side of the star’s emission and then move over to the other side,” Dr. Prato said.

“When a planet transits a star, you can determine the orbital period of the planet and how fast it is moving toward you or away from you as it orbits. So, we said, ‘If the planet is real, what is the velocity of the planet relative to the star?’ And it turned out that the velocity of the planet was exactly where this extra bit of H-alpha emission was moving back and forth.”

“Transit observations revealed that the planet is only about 3 – 4% the size of the star, but the H-alpha emission from the planet appears to be almost as bright as the emission coming from the star,” Dr. Johns-Krull said.

“There’s no way something confined to the planet’s surface could produce that effect.”

“The gas has to be filling a much larger region where the gravity of the planet is no longer strong enough to hold on to it. The star’s gravity takes over, and eventually the gas will fall onto the star.”

Details of the research were recently accepted for publication in theAstrophysical Journal. The article is also publicly available at arXiv.org.

Source: Scie-News