Two red circles stare out at me from the gnarled black trunk of a stumpy tree. Eyes. A face. It seems to look me over critically: “Are you regretting this yet?”

It’s very early, deserted, completely silent. No birds, no cicadas, no hint of breeze. When there’s a tiny rustle, I’m suddenly transfixed by another pair of eyes, above me on the path. I’m nonplussed. All I know about wild boar is ravioli al cinghiale: faced with this small but ferocious-looking female, with two cartoon-cute piglets cuddled into her flanks, I don’t know the etiquette. Which of us is supposed to turn and run? After a moment she lumbers huffily off into the undergrowth, leaving me feeling somehow reprimanded. It’s her place, this “Parco di Portofino”, a wilderness that stretches right across this peninsula.

Suddenly the clouds part, a weak morning sun breaks through, and right on cue the cicadas start their racket. The metallic sea hundreds of feet below me gives a sudden shudder as the cloud passes, and turns deep, dreamy blue. I urgently wish that instead of sweating along this hard path, I was having my first swim from the pebbly beach back at San Fruttuoso.

…

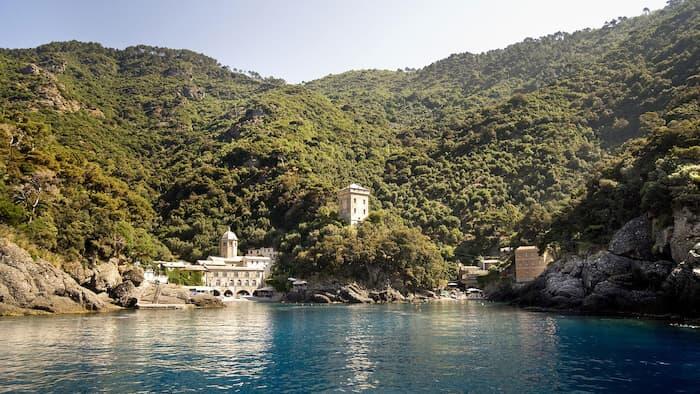

There are few places like it. The wooded Capodimonte hills plunge steeply down into the water all along this coast, making its tiny bays inaccessible except from the sea. San Fruttuoso sits on one of the small inlets and is the site of a small Benedictine abbey, part medieval, part Romanesque, built to preserve the remains of an obscure Catalan saint, and perched so close to the water’s edge that its arcaded base serves as a refuge for fishing boats. A defence tower was added on the facing hill in the 16th century by the Doria Pamphilj family, lords of the region, and later roofed over to become a dwelling. A scattering of cottages cluster behind the abbey buildings, remnants of a community that once fished here, or herded sheep and pigs and grew olives, vines and fruit, or milled flour from the local chestnuts.

There is still no way to reach San Fruttuoso by road, so the boats that run to and from Camogli, up the coast to the north, and in the summer season back and forth to Portofino further south, are the only access. Daily, in the summer, a tide of visitors arrives on the first boats to fill the two pebble beaches, to eat fish and seafood at the three restaurants nestling into the cliffs, or for deepwater swimming, snorkelling and diving.

There is something special for divers here. In 1954, a two-metre bronze statue of a robed “Christ of the Abyss” was submerged 15 metres deep into the water just off the shore — to bless the sea and those who make their living from it. And to bring the lifeline of tourism. It’s a strangely unsettling sight, just visible from my snorkel (I don’t do airtanks) when a shaft of sunlight catches the upturned face and outstretched arms: a more efficient viewing for those who don’t dive is from a glass-bottomed boat that makes the trip.

By day at San Fruttuoso, there’s the usual beach chatter and clatter across the sunbeds packed in Italian-style tight. Visiting the beautifully restored abbey is a curious experience: here are cloisters, colonnades, vaulted rooms, medieval tomb-niches in multicoloured marble, the underground remains of an even older church — all set to the sounds of families playing on the beach right under the austere gothic windows.

But as the late afternoon sun moves behind the hill and the last boats leave, taking all but a handful of people, a deep silence falls on San Fruttuoso. From the high terrace of our small cottage we could hear nothing but the soft shush of the waves on the pebbles, a cat purring, a low murmur of conversation at the other side of the bay. I’ve seldom experienced quiet like it.

In summer, a couple of the restaurants do stay open in the evenings — except on Sunday nights, when you are truly on your own. There is no food shop, so if, like us, you stay in the only self-catering cottage, and forget to bring in what you need, that’s it.

The cottage — Casa de Mar — is one of a pair built immediately behind the abbey in the 18th century, and restored a few years ago by Fondo Ambiente Italiano (FAI), the state-owned Italian heritage trust. It has been tastefully refurbished this year by the Landmark Trust — with whom FAI now shares the management of the cottage — with simple tiled floors and dark wood antique-type furniture. Two comfortable bedrooms overlook the abbey’s bell tower and the shore beyond; the small kitchen is well-equipped; there’s no television nor WiFi, no frills. You need to like reading, and quiet, and the person you’re with.

It’s odd, perhaps, that a British charity devoted to preserving significant historic buildings in the UK should take on this remote property. The few other Italian properties in the Landmark Trust portfolio have strong British cultural associations — the flat in Rome above the one in which Keats died; Robert and Elizabeth Browning’s former home in Florence — or a grand pedigree such as the former summer residence of the bishops of Padua. The San Fruttuoso cottage is charming, but hardly special in itself, and neither the settlement nor the patron saint whose mosaic portrait presides over the quay have any obvious British connections.

But the place … it is truly special. The boats from Camogli and Portofino are packed mostly with Genovese and other Italians from the area, who cherish San Fruttuoso’s beauty and atmospheric combination of qualities: it seems half shrine, half playground. A toytown version of a medieval holy place together with the perfect beach experience (and pretty good food): except it’s not quite that, either. You can sense, as the sun leaves this deep bay, how harsh the winter might be, how lonely this tiny settlement was, how tough the surrounding mountains still are.

…

Back up on the clifftop, the sun is high now and the heat is building up. The walking alternates between gentle paths and harsher terrain — slithering down a vicious stony screed into a deep gulch, only to scramble and sweat up the other side — but the dramatically gorgeous landscape, the sea far below, and the dreamy scent of flowering myrtle (the true smell of the Mediterranean maquis) makes every scrape worthwhile. The red eyes are my best friends now, staring at me quizzically at every turn. “Happy now?” they ask.

I smell human life before I see it. Cigar smoke. Around the next bend is a garden cut into the cliff, a riot of hydrangea, vines, oleander, roses, olives, geraniums, and its owner, his cheroot clamped in his teeth, busy digging a tiny terrace plot on which perches a single lemon tree. When I ask him how far it is to Portofino he takes one look at me, decides I’m in need of a comforting fib, and replies, “20 minutes”.

At least 45 minutes later, as I finally clamber down, down, down the hill into Portofino, it seems that just a couple of hours high on the cliffs after a night in San Fruttuoso’s monastic quiet have made a mountain woman of me: the famously chic and pretty port town holds no charm. Dior? Longchamps? These surging crowds in their expensive sunglasses? That ludicrous giant yacht blocking the view across the harbour? Bah. I find the boat back to San Fruttuoso, and set my face firmly out to sea.

Jan Dalley is the FT’s arts editor

Photographs: Jan Dalley

Source: Financial Times