Humanity’s great leap into the space between the stars has, in a sense, already begun. NASA’s Voyager 1 probe broke through the sun’s magnetic bubble to touch the interstellar wind. Voyager 2 isn’t far behind. New Horizons shot past Pluto on its way to encounters with more distant dwarf worlds, the rubble at the solar system’s edge.

Closer to home, we’re working on techniques to help us cross greater distances. Astronauts feast on romaine lettuce grown aboard the International Space Station, perhaps a preview of future banquets en route to Mars, or to deep space.

For the moment, sending humans to other stars remains firmly in the realm of science fiction—as in the new film, “Passengers,” when hibernating travelers awaken in midflight. But while NASA so far has proposed no new missions beyond our solar system, scientists and engineers are sketching out possible technologies that might one day help to get us there.

NASA’s Journey to Mars, a plan aimed at building on robotic missions to send humans to the red planet, could be helping lay the groundwork.

“Propulsion, power, life support, manufacturing, communication, navigation, robotics: the Journey to Mars is going to force us to make advances in every one of these areas,” said Jeffrey Sheehy, NASA’s Space Technology Missions Directorate chief engineer in Washington, D.C. “Those systems are not going to be advanced enough to do an interstellar mission. But Mars is stepping us that much farther into space. It’s a step along the way to the stars.”

Charting the unknown

Hurling ourselves, Passengers-style, just to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, would require crossing almost inconceivably vast distances. We would need truly exotic technology, such as suspended animation or multi-generational life support. That places in-person visits well out of reach, at least for the near term.

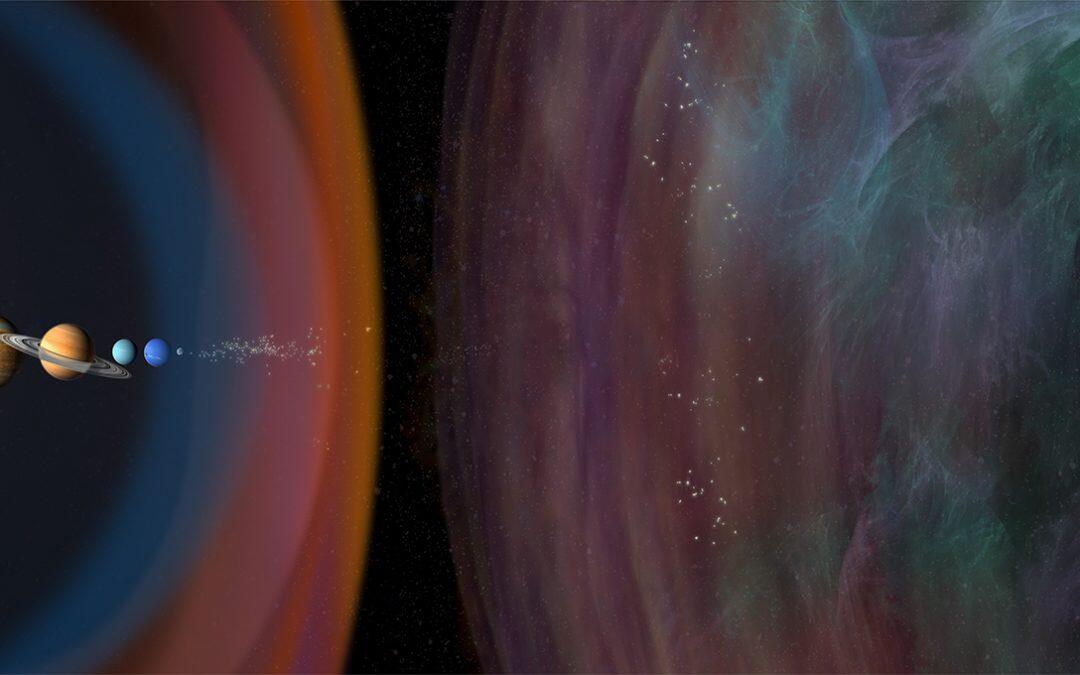

But the possibility of robotic interstellar probes is coming into much sharper focus. Space probe pioneers say the radiation, energy and particle-bathed space between the stars—the so-called interstellar medium—is itself a worthy science destination.

“We need more explorers, more of these local probes into this region, so we can understand better these interface conditions between our sun and the interstellar medium,” said Leon Alkalai, an engineering fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and co-author of a 2015 report on exploring interstellar space. “Like the ancient mariners, we want to start creating a map.”

Alkalai’s report, “Science and Enabling Technologies for the Exploration of the Interstellar Medium,” maps out the knowns and unknowns of largely uncharted regions, from the dark, distant, dwarf worlds of the Kuiper Belt to the “bow shock”—the turbulent transition thought to separate the sun’s bubble of plasma from the interstellar wind. Drawing on the work of more than 30 specialists during two workshops at the Keck Institute for Space Studies, the report poses pressing questions about the structure, composition and energy flow in this cosmic vastness. And it paints one of the most detailed pictures yet of a possible interstellar probe using present-day technology.

Read more on NASA