It was meant to be a neighbourly get-together – but the takeover of the UK’s Streetlife website by America’s Nextdoor has left many British users deeply unhappy with the new arrangements.

It has also revealed a transatlantic cultural chasm in attitudes to privacy.

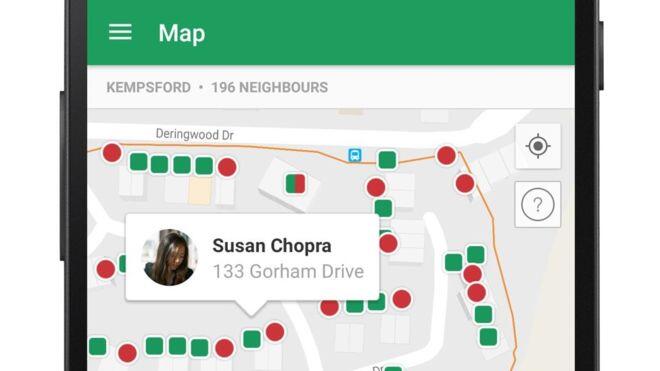

Nextdoor describes itself as a private social network, but one where people give their real names and addresses.

That’s rather different from Streetlife, where people are generally John from Acton, rather than John Smith from 225 Acacia Gardens.

Shock

On Monday, Streetlife members received an email announcing the deal and inviting them to transfer to Nextdoor.

It was made clear that Streetlife would be shutting down as a social network in a fortnight, so there was not much incentive to stay.

But when they clicked on the big button in the email enabling the move to Nextdoor, some users – indeed rather a lot if my Twitter messages are anything to go by – were horrified.

Seeing a directory of the full names and addresses of people in their new Nextdoor neighbourhoods was a shock.

Risk

Some felt that this new level of visibility had not been made clear – and indeed in the email I received as a Streetlife member there was no clear explanation of this vital difference between the two networks.

Tony Sutton says: “I switched to Nextdoor and instantly closed my account – full address shown without telling me before I signed up.”

Others thought the publication of this information had put people at more risk of identity theft, although Nextdoor stresses that user details are available only within your neighbour network, and – unlike Streetlife – any discussions are not searchable via Google or other search engines on the wider web.

But one Streetlife user had a good reason to be very angry about the way the transfer worked.

Secret

This woman – who I won’t name for obvious reasons – was a member of a Streetlife community, as was her violent former partner.

He did not know her new address, and she’d done her best to keep it secret.

Then, on Monday, the invitation to move to Nextdoor arrived.

“Quite a few people moved over in our area straight away – my ex and I being two of them,” she says.

“As we were some of the first, it took a while for people to notice that everyone’s full address was visible as the default.

“By then, the damage was done.

“I obviously changed my settings as soon as I could – but too late.”

Fuss

Now, her former partner has been in touch to say he knows where she lives.

She complained to Nextdoor but was unhappy with the response she received.

Nextdoor says its response was “immediate, polite and appropriate”, but it apologised unreservedly to anybody who had been distressed.

The company told the BBC: “Nextdoor is a private network: members’ identities are only visible to immediate, verified neighbours, and cannot be searched for or discovered on the internet.

“We put users firmly in control of managing their privacy settings, and over 90% of users choose to show their real identity and address.

“We are striving to clearly communicate the differences between Nextdoor and Streetlife to allow people to decide whether to sign up for Nextdoor, and this is an entirely voluntary process.”

Lax

The company says 150,000 communities across the United States enjoy the way Nextdoor works, but accepts that a minority of Streetlife users will decide that it is not for them.

One user, Paul Blitz, says that is due to a difference in attitudes to privacy.

“I get the feeling that Americans are much more lax about their data protection, more willing to give out personal information,” he tells me.

“In the UK, we seem to be more careful.”

What does seem clear is that Nextdoor’s approach has proved more commercially viable than the one adopted by Streetlife.

That means British users will have to adapt to an American view of privacy – or find another way of connecting with their neighbours.