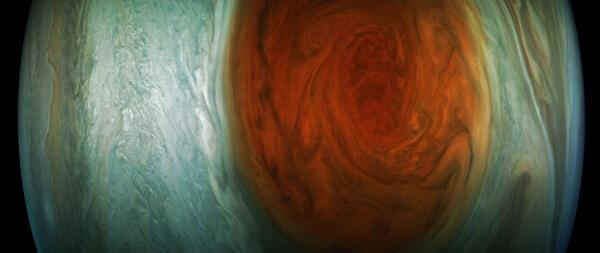

The pictures the probe returned are stunning. As it passed over the Great Red Spot at a height of 5,600 miles (9,000 kilometers), Juno’s imaging camera, JunoCam, snapped several apple core-shaped photos of the feature in optical light. But pretty pictures weren’t Juno’s only goal; all of the spacecraft’s eight additional instruments recorded data during the flyby as well. Those instruments include a magnetometer, a radio and plasma wave sensor, a microwave radiometer, and an ultraviolet spectrograph. By combining the multi-wavelength data from these state-of-the-art instruments, scientists can create a more complete model of the storm than ever before.

“These highly-anticipated images of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot are the ‘perfect storm’ of art and science. With data from Voyager, Galileo, New Horizons, Hubble and now Juno, we have a better understanding of the composition and evolution of this iconic feature,” said Jim Green, NASA’s director of planetary science, in a press release.

“For hundreds of years scientists have been observing, wondering and theorizing about Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. Now we have the best pictures ever of this iconic storm,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Although he added that it will take time to sort through and analyze the influx of new data, the details Juno is returning are vital to understanding the storm’s dynamics, both past and present.

The July 10 flyby was Juno’s seventh close approach to the planet; in total, it will orbit Jupiter 37 times, with the closest pass bringing the spacecraft within about 2,100 miles (3,400km) of the cloud tops. At mission’s end in 2018, Juno will plunge into the planet’s atmosphere, just like the Cassini mission currently orbiting Saturn.