Defining what makes an apple “heirloom” — and deciding when it’s simply old, or pocked, misshapen or colored outside the norms of commercial apple production — is open to debate, even within the apple community.

“The term ‘heirloom’ is in the eye of the beholder,” said Julia Stewart, spokeswoman for the New York Apple Association.

There is no formal definition of what an heirloom apple is, but most orchardists and growers would count the apples that come from cultivars of antiquity as heirlooms. The apples that our great-grandparents would have grown and harvested for pie or cider fall under the umbrella of “heirloom,” and while many have fallen out of favor, replaced by fruits with snazzy names like RubyFrost and SnapDragon (which can be grown only in New York), Macoun, McIntosh, Cortland and Jonagolds are some examples of heirlooms that continue to thrive in popularity.

The use of the moniker “heirloom” is nearly as debatable as the definition. “The term ‘heirloom’ to people in the apple world is considered faux pas,” said Alejandro del Peral, an owner of Nine Pin Cider in Albany. Many apples are falsely referred to as heirloom because of appearance or taste (akin to heirloom tomatoes, which often includes anything not round or red). Some prefer to call these older apple varieties “heritage” or “antique.”

Confused?

“It’s such a complicated subject. It’s going to take a while for people to understand it,” said del Peral, of the process of growing and breeding apples. Perhaps the best way to make sense of it all is to compare apples to humans, at least from a genetics standpoint.

Just as each human is a genetic individual, so, too, is each apple seed. Taking half of its DNA from the mother tree and half from the pollen father, each seed offers a chance to develop a new variety. Replications of “true” trees that will continue to bear a desired apple are propagated through the art of grafting or cutting a twig from one tree and splicing it onto the rootstock of another.

Trees that grow and continue to produce fruit for as much as a century or more are considered antique apples. If someone names those apples and finds them to be desired for flavor or appearance, a sample branch may be trimmed from the tree and grafted onto rootstock. Those apples become “heirloom,” with grafts from the initial tree being passed down like a quilt through the generations. Apples that grow from the seeds of those antique or heirloom apples are “heritage” apples, having properties of their ancestors but becoming a unique genetic specimen, just as green eyes and curly hair might be passed down in humans.

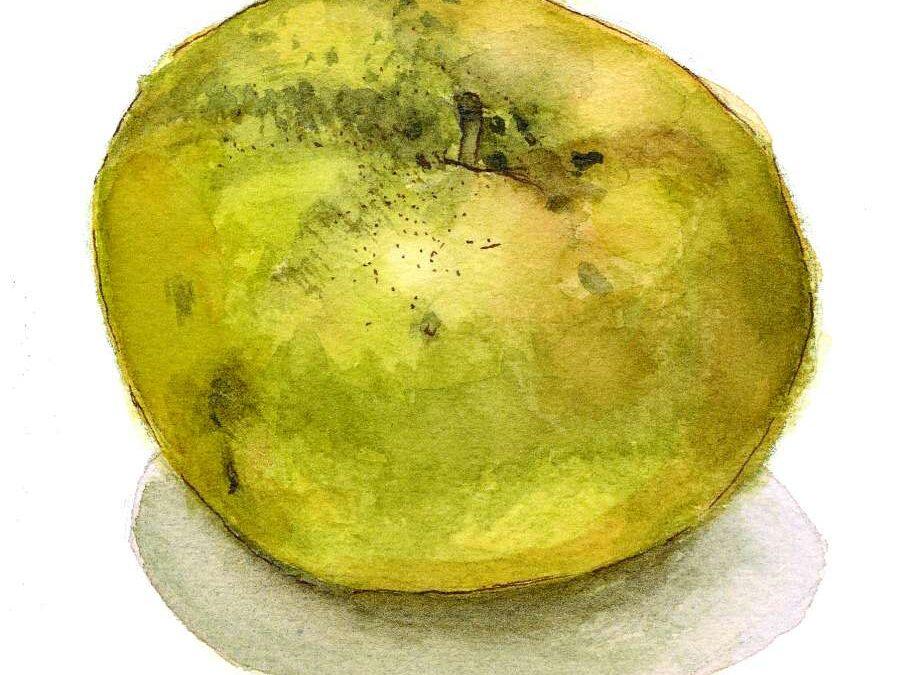

Walking among the apple trees at Samascott Orchards, in Kinderhook, helps to illustrate these groups of apples. Favorites like gala, Fuji and golden delicious, are produced in droves, but hidden groves of trees expand the apple repertoire. Jake Samascott and del Peral have worked together to find and identify apples suited for cider-making, whether they be established heirlooms like golden russet, Kingston black, Ashmead’s kernel or wild “chance seedlings,” as Samascott calls them, to create a designated cider orchard. It includes 400 young trees that the duo started from seeds that were selected from mother fruit good for cider.

“I personally think every day how fortunate I am to have partners like that,” said del Peral, of Samascott. (Of the approximately 1.5 million pounds of apples Nine Pin will use this year, 95 percent come from Samascott Orchards.) This year is the first Nine Pin will press some of the old English bittersweet varieties (like Yarlington mill) from Samascott. Del Peral also harvested wild crab apples the size of marbles with a team of cidery workers and local chefs and restaurateurs to make a special cider that will be available only to those restaurants and at Nine Pin’s tasting room.

Samascott said his apple program is a bit different than conventional breeding programs “looking for the next Honeycrisp.” He added, ”It’s a much more controlled experiment than ours. We’re taking more of a Johnny Appleseed approach.” His orchard grows 70 varieties of apples for commercial markets, totaling 40,000 bushels this year, a good but average yield.

Michael Guidice, of Brick House Homestead orchard and cidery in Sharon Springs, said this approach to discovering, maintaining and developing apples is “folk taxonomy mixed with science.” While he grafts Yarlington Mill and other heirloom apples onto rootstock, he also seeds his expansive farmland with a mix of sheep bedding, soil and pomace (the remnants of apples after pressing for cider), which has resulted in hundreds of new seedlings, each a unique cultivar of apple.

The heirloom and heirloom-approximate boom comes at what Guidice calls “an epoch of American cider.” As cider becomes a staple in the craft beverage movement, the desire to find new flavor components to blend has spurred the quest to preserve heirloom varieties and propagate seeds from favorite apples. Still, of the 28 million bushels the New York Apple Association estimates growers will produce this year, heirlooms will be but a fraction.

“Heirloom apples are a small but important part of the industry because they speak to the rich history of apples in New York state, which first appeared in the 1600s with the first European settlers,” Stewart said. “No one tracks data beyond the most popular varieties so we can’t speak to the percentage of crop heirlooms account for.”

Regardless of what they are called, these old cultivars of apples — found, fostered, or otherwise — will be embraced if they produce fruit perfect for a ploughman’s lunch, an apple crisp or pressed into crystalline cider.

Source: http://bit.ly/2yGzjtX