The leaders of ancient Egypt knew a thing or two about natural disasters.

Handle a famine or drought badly as pharaoh, and you could have empire-wide revolt on your hands.

A new study shows how big a role climate change and natural disasters likely played in sparking such political uprisings. And it suggests that despite frequent famines, the Egyptian rulers failed to grasp just how vulnerable they were to environmental devastation right up until the day their empire collapsed. It is a lesson contemporary leaders may find both instructive and alarming as they increasingly cope with one freakish weather event after another, from devastating hurricanes to wildfires.

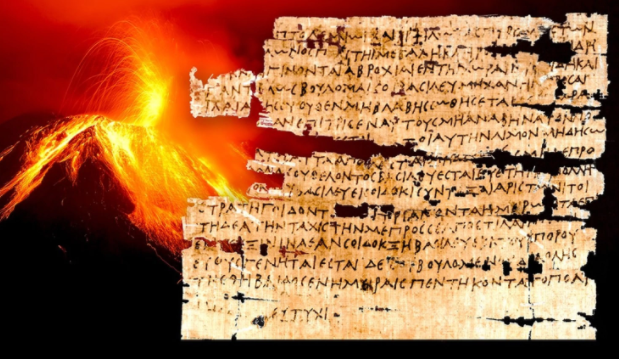

The study — published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications — combines ice core dating of ancient volcanic eruptions with papyrus records of uprisings to show that each time there was a volcanic eruption during Egypt’s Ptolemaic period, it led almost inevitably to unhappiness and revolt.

“It shows there are real political and societal consequences to environmental changes like global warming and disasters,” said Joseph G. Manning, a historian at Yale University who led the study. “We act as if these things won’t affect us. But when you see how advanced civilizations of the past could at times be pushed over the edge by events like these, it suggests that we should be treading lightly on the Earth.”

Egypt during the Ptolemaic age — from 305 to 30 B.C. — was a flourishing cultural and military powerhouse. Its kings were the successors to Alexander the Great’s empire. They created the Library of Alexandria and built the city’s shining lighthouse — one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

But the Ptolemaic Empire was also deeply dependent on crops watered by the summer flooding of the Nile. During years when that flooding didn’t happen, harvests were devastated and there was famine and civil unrest.

What the Ptolemaic kings didn’t know was that those dry years were often caused by volcanic eruptions, sometimes as far away as the other side of the world, that sent up sulfates into the atmosphere and caused dramatic changes to global weather patterns.

The team behind Tuesday’s study created a timeline connecting that climate change to political revolts using data gathered across a wide range of scientific fields.

Especially key to their work was newly emerging ice core data that has revised the dates for when major volcanic eruptions occurred. Last year, one climate expert who had been part of such ice core redating work, Francis Ludlow, happened to be at a dinner at Yale University with Manning, when Manning began rattling off dates of revolts during the Ptolemaic period that historians have never been fully able to explain.

“As he was listing off these dates, it was triggering all sorts of things in my mind from the ice core data,” Ludlow said. “We started comparing them, and it was amazing how the revolts were matching up exactly with the eruptions.”

Their team pulled in an expert on monsoon weather who connected the volcanic eruptions to the water levels of the Nile. They connected all that data with meticulous ancient records of the Nile’s water levels and papyrus records of political upheaval. And they used statistical modeling to show that the frequency with which volcanic eruptions matched up to political revolts put it far beyond a matter of chance.

“The basic mechanisms they’re using for the work are established and sound,” said Michael McCormick, a medieval historian at Harvard University, who was not involved in the study. In recent years, McCormick has published similar research connecting volcanic eruptions to famines and upheaval during the reign of Charlemagne in Western Europe.

Such work is part of a new body of research emerging from collaborations between experts in fields like genetics or climatology and historians who previously focused more on written records and archaeology.

Virologists and geneticists, for example, are now teaming up with historians to reconstruct genomes of ancient diseases to understand how they drove historical events. The study of physical data — such as ice cores, tree rings and pollen grains — has yielded especially exciting theories and new understanding of environmental effects on the collapse of ancient societies like the Roman Empire and the Mediterranean’s Bronze Age civilization.

“The lesson I draw from all of this is how much we need to have humility,” McCormick said. “We’re talking about civilizations that lasted a long time, that were just as smart and able and enterprising as we are. And yet, they were sometimes dealt devastating blows by the environment. Sometimes they were able to overcome them, but sometimes they were overcome by them.”

Some Egyptian leaders appear to have conducted disaster relief better than others, possibly forestalling revolts in their time.

One of the largest volcanic eruptions in the last 2,500 years occurred during the rule of the famed and final Ptolemaic leader Cleopatra. It caused a time of plague, famine and drought. Yet, there is no record of political revolt, the study notes.

Part of that may have to do with Cleopatra’s speedy steps toward disaster relief, some of the co-authors theorized. According to historical records, Cleopatra opened up state granaries and instituted tax relief. In the end, however, it did not save her nor the Ptolemaic Empire. In 31 B.C., when the Romans defeated Cleopatra’s navy, her empire had already been weakened for years by the Nile’s failing waters, famine and plague. Soon after, she committed suicide.

Manning, co-author of Tuesday’s study, said he sees another historical lesson in the fall of Cleopatra and the Ptolemaic Empire. “For so long, they had been playing so close to the edge, fighting huge wars and growing crops that were especially vulnerable to changes in the Nile. They refused to change their politics and it left them vulnerable once larger forces in nature and in the world came along and pushed them over the edge.”

Source: http://wapo.st/2zQve3X