U.S. giants can suck up tech talent with compensation packages that startups can’t match

Recent moves by U.S. technology giants Meta, Google and Amazon to significantly beef up their presence and staffing levels in Canada have cemented the country’s status as a growing hub for technology talent.

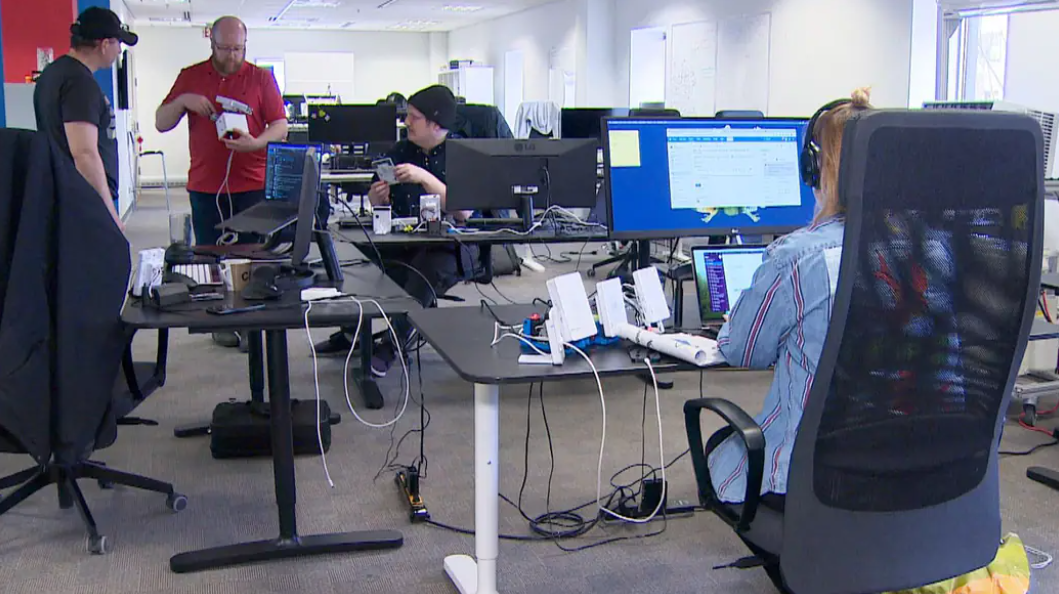

While Canada’s tech boom may be welcome news for those who dream of working for these tech giants, it comes at a cost for local startups, which suddenly have to compete with foreign Goliaths for the country’s best and brightest.

“The more companies are being created and built, the more pressure there is,” said Jeremy Shaki, co-founder of Lighthouse Labs, a Toronto-based technology education company that offers coding boot camps and other services for people looking to level up their careers.

Shaki says it’s no secret why large foreign tech firms are eager to set up shop in Canada; beyond the access to new customers, Canadian universities are cranking out skilled workers at a rapid clip — and they often come at a fraction of what they would cost in places like Silicon Valley.

In late March, Meta (formerly known as Facebook) announced plans to hire up to 2,500 people in Toronto and in other parts of Canada, while Google says it’s looking to triple its workforce here. Amazon wants to hire for some 600 tech jobs.

But in pure financial terms, these companies have the resources to outbid everyone else when it comes to securing the right person, and that can make things difficult for local firms trying to compete.

More than just money

Ron Spreeuwenberg faces that challenge every day. He’s the CEO of HiMama, a software company founded in Toronto in 2013. HiMama makes software solutions for the child-care industry and employs roughly 180 people, more than half of whom have been hired in the past two years.

Now boasting 10,000 customers, the company has expanded its hiring pool well beyond their home base of Toronto, with staff across Canada and the U.S.

Canada’s days of being little more than a source of cheap coders are over, says Spreeuwenberg.

“I think we had a period of time where we were lucky, where we could find really great quality talent at lower compensation rates,” he said in an interview. “But people have found out about us and it made it challenging.”

The biggest thing Spreeuwenberg says he hears time and again from new hires is that they want the opportunity to grow and develop their skills. “The No. 1 reason why people choose a company or a role is what the company does and the opportunity for them, in terms of learning and development, and the challenge,” he said.

That said, he acknowledges money helps. “We know we’re competing against companies … who certainly can afford a lot more than us when it comes to compensation.”

Spreeuwenberg says a major selling feature for recruiting would-be hires to HiMama from outside Canada is the country itself, as is the opportunity to work toward the company’s goal of improving childhood development.

“Those are very important for us and things that a lot of our employees care deeply about,” he said.

That desire to do good work and help solve problems is a major theme at another Canadian startup, Mysa, based in St. John’s. Founded as a Kickstarter project in 2016, the smart thermostat company has grown from just two employees at launch to more than 100 across Canada today, serving more than 150,000 customers.

Just as Shopify is synonymous with Ottawa, and BlackBerry is to Waterloo, the 800-pound gorilla of the technology sector on the East Coast is Verafin, a St. John’s-based cybersecurity firm that made headlines last year when it was bought by Nasdaq for nearly $3 billion.

While not a household name in the rest of Canada, Verafin’s successes have shone a light on the region’s booming technology sector, said Mysa co-founder Joshua Green.

That means he, too, is dealing with the same compensation conundrum other startups face: It’s hard to compete with deep-pocketed big tech.

But just as HiMama appeals to people looking to live in Toronto, he’s able to make a similar pitch.

“That quality of living, of being able to work for a technology company while also living in a place like Newfoundland and Labrador, is appealing to not everyone, but a growing number of people,” Green said.

“And the No. 1 reason why I think people want to join — our mission and the purpose of why we exist as a company — is to fight climate change.”

Investment money pouring in, too

The HiMamas and Mysas of the world aren’t just attracting the attention of tech giants like Google, Meta and Microsoft when it comes to hiring; they’re also attracting U.S. investment dollars.

HiMama recently secured $70 million in funding from Boston-based private equity firm Bain Capital — a sign of just how on the radar Canada’s tech ecosystem has become.

“There’s a lot of interest from investors outside of Canada in Canadian companies because of the talent and the quality of the startups,” said Craig Leonard, a partner with venture capital fund Graphite Ventures.

“But also, they are relatively less expensive at times than some of the companies who would be built in, in some of the other ecosystems, [like] say, in the United States.”

According to a recent report from commercial real estate firm CBRE, Toronto is the third-largest technology hub in North America. Ottawa and Vancouver also rank in the top dozen, well ahead of places like Austin, Texas, Portland, Ore., and Chicago.

Though it may be hard to believe, there are more tech workers in Toronto than there are in Seattle, which is home to Amazon and Microsoft.

Not that long ago, lower salaries would have been a major selling point for a U.S. tech company looking to establish a beachhead in Canada. But the pandemic changed things some, as the shift toward virtual offices allowed Canadian companies to attract talent from around the world.

“It also levelled up the salaries and the opportunity for Canadian talent to go and work for other companies,” said Leonard.

For Dr. Alexandra Greenhill, the CEO of Vancouver-based health-care-focused artificial intelligence firm Careteam Technologies Inc., a little healthy competition is good for everyone, making companies of all sizes better, while also spurring on the next generation of startups.

“If we do this right, it could be a very positive thing for the country,” she said in an interview. “But if we don’t do this right, it can be a disaster.”

Greenhill said she recently lost a handful of great people to Amazon, after it set up shop in her backyard of Vancouver and were “offering two to three times the salary that I offer my engineers.”

While she doesn’t begrudge anyone for leaving, she’d like to see large rivals invest a little more in training less experienced workers, as opposed to simply hoovering up a local talent pool that’s been painstakingly created over time.

“We can give them all kinds of perks and interesting things to do and whatnot, but the pure dollars are just completely out of our league and drive all the prices up,” she said.

Though Greenhill admits it’s a constant struggle, she’s optimistic about Canada’s tech future, because she can see what’s possible when the right environment is created — one that encourages foreign companies to come in and participate in the ecosystem, rather than just take from it.

She’s on the board of Canada’s Digital Technology Supercluster, a government-led initiative seeking to fast track Canada’s status as a digital hub. Greenhill says the initiative combines the carrot of government cash to fund tech projects, with the stick that strings come attached to that money.

Specifically, foreign tech giants wishing to participate have to invest themselves and set up roots, too.

“They have a role to play in making the ecosystem a better, stronger place,” she said.

A rising tide lifts all boats

With the backing of government, the supercluster initiative plays something of a convener role, Greenhill said, holding big tech “accountable for their commitments and inviting them to behave like good corporate citizens.”

And instead of seeing big tech as an adversary, they can help to cross-pollinate the whole ecosystem. “They set up accelerators, they become mentors, they create joint projects with the local companies,” she said.

To the investment community, dollars and cents will always be top of mind, but Graphite’s Leonard says the best outcome for Canada’s tech sector is one where there’s a lot of collaboration and competition.

“If you get that consistent investment … it creates a flywheel effect of anchor companies that then develop that talent,” he said. “They start companies, those companies exit, that talent goes back into the pool, as well as investment dollars.”

Without that collaboration and long-term commitment, there will be no rising tide to raise all boats.

“If we don’t do anything, you can end up being a country that just exports talent,” Greenhill said.