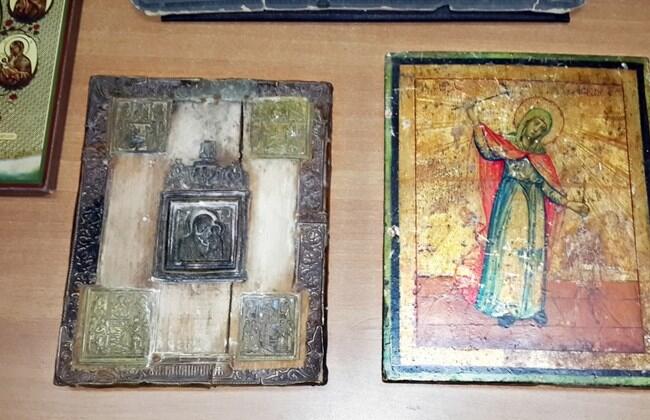

Seized by Lebanese security forces at the airport, ports and at the land border with Syria, trafficked objects are sent to the Directorate General of Antiquities, part of the Culture Ministry. Seized objects are carefully cataloged and stored in warehouses under the protection of armed guards. “We have many warehouses. For security purposes we don’t usually say where, but we have several warehouses and they are well guarded.” Lebanon’s vigilance in the face of widespread looting and trafficking of cultural goods is a rare point of light in an otherwise bleak regional panorama. Aside from killing untold numbers of civilians, the jihadi group ISIS has destroyed ancient relics in Iraq and Syria which it perceives as idolatrous. According to a report issued by the inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force earlier this year, ISIS also sells stolen antiquities and taxes traffickers who smuggle the artifacts through territory controlled by the group. Last month, ISIS took control of Palmyra, an ancient city and UNESCO World Heritage Site that has a history of inhabitation dating back almost 10,000 years. The smugglers who traffic antiquities through Lebanon are “criminals and they are participating in one way or another in financing terrorism,” Areiji said. ISIS is not the only group engaged in looting, however. According to FATF, 90 percent of Syria’s cultural artifacts are located in areas affected by the ongoing civil war, and “large-scale” smuggling has emerged in many areas. “Many international [smuggling] mafias, they work now in Syria,” said Ahmad Deeb, Syria’s director of museum affairs on a recent trip to Beirut. Despite the precarious situation Syrians and their cultural heritage face today, Deeb was in Beirut under more auspicious circumstances: The Lebanese authorities have recently intercepted a number of stolen artifacts believed to be of Syrian provenance. “We’ll look at the objects to determine if they are [genuine] or not, and return these objects back to Syria,” he said. A number of religious icons stolen from the Syrian village of Maaloula were among the items found. Dating back a few hundred years, the items are not archaeological pieces but, according to Areiji, the icons are important to preserve. “We’re not confining our actions to antiquities,” he said. “We are also dealing with objects that I might consider of patrimonial [value].” Aside from the Maaloula icons, Areiji said that everything from paintings to “windows from houses in Homs and Aleppo” will be repatriated to Syria in due time. “We consider these things to belong to the cultural heritage of another country,” Areiji said. The icons, kept in a padlocked basement room in the Directorate of Antiquities, include an 18th-century wood cutting and an old photograph of a clerical gathering at Maaloula. “I don’t know who the thieves are. I don’t want to know,” said Anne-Marie Maila-Afeiche, the curator of the National Museum in Beirut, gazing at the recovered objects. “For me, it’s just that we had the chance to help,” she explained. “We will do whatever we have to do in order to give them back.” Afeiche said that she receives notices from Interpol “every other day” about the theft of cultural goods from Iraq and Syria. This is not the first time items stolen from Syria during the civil war have been returned after being seized in Lebanon. Several months ago, Deeb traveled to Beirut and returned to Syria with 69 artifacts, including ancient mosaics and stone relics taken from Apamea, an archaeological site in Hama province. While many stolen antiquities seized in Lebanon have been identified and returned, Areiji said that establishing the origin of artifacts is a difficult task. Often objects that appear were excavated illegally during the chaos of war. “We have a lot of antiquities, but we are not able to determine [their origin],” Areiji explained. “It’s a big problem.” Items of indeterminate origin are kept in Lebanese warehouses until more identifying information arises. The culture minister and the director-general of antiquities work in close collaboration with their colleagues in Iraq and Syria to allow for the identification and repatriation of cultural goods. The collaboration, Areiji stressed, is strictly a matter of preserving culture. “For me, it’s not a political matter,” he said of working with Syrian and Iraqi counterparts. The safeguarding and ultimate repatriation of artifacts is part of what Areiji calls “cultural resistance” against those who wish to destroy the region’s history and diversity. Having suffered from more than 15 years of civil strife, Lebanon is well suited to shield cultural artifacts from the scourge of war, Maila-Afeiche said. “We learned the hard way,” she added. Elise Knutsen| The Daily Star