When Dr. Brian Morgan moved to Fresno, California, a decade ago, the frequency of babies being born too early in his new community struck him. So did the widespread pollution —freeway exhaust, processing plant emissions, pesticide-tainted soil stirred up by the agricultural region’s fleet of tractors.

“If you park your car in Fresno, it’s gonna get a layer of dust on it,” said Morgan, a specialist in maternal-fetal medicine at the University Women’s Specialty Center in Fresno. “I began to wonder, and still do wonder, whether environmental pollutants are a factor here” in the number of preterm births.

Fresno has one of California’s highest rates of preterm births — which means a baby arrives at least three weeks before their due date — at around 10 percent. The city also ranks among the dirtiest on state and national lists.

Morgan could be on to something, according to a video released today. Even mild exposures to some contaminants may raise a pregnant woman’s risk of delivering her baby too soon, warns the four-minute production.

The video draws on emerging scientific evidence that particulate matter, lead and other pollutants — especially in combination, as they’re typically encountered — may play a role in the approximately 15 million babies born preterm every year around the world.

Because these [toxics] are insidious, or invisible, they are easily dismissed or ignored. But they can have grave effects on pregnancy and a child’s development,” Bruce Lanphear, an environmental health expert at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, says in the video.

Nearly one in 10 babies in the U.S. is born preterm. About half of these early arrivals cannot be explained by known risk factors, such as multiple births, poor nutrition or infections. Lanphear and other experts say environmental toxics are generally overlooked and could be contributing to the nation’s staggering rate — among the highest in the developed world, even rivaling some developing countries.

The stakes are significant. Babies born prematurely face serious challenges, from uncertain survival through the first weeks of life to greater risks for future medical troubles including diabetes and heart disease. A study published in October warned that fewer weeks in the womb could derail brain development, potentially setting a child up for learning, attention and psychiatric problems.

The toll on society is troubling as well: Preterm births cost the U.S. economy an estimated $26 billion every year.

But there is some good news. Recognizing and targeting preventable exposures to environmental toxics, suggests Lanphear in the video, could “result in a big reduction in preterm births.”

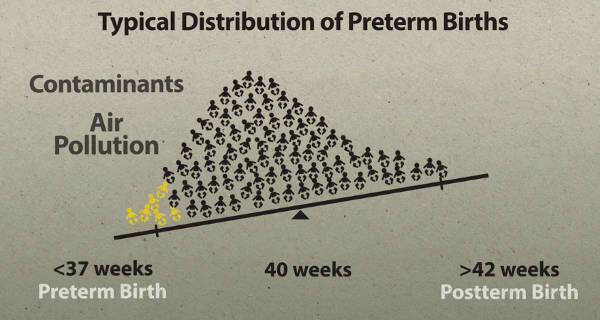

While a pregnant woman’s exposure to small amounts of any single toxic may trim her child’s time in the womb by only three to seven days, he explains, the toll from multiple exposures can add up.

“If we really want to prevent preterm birth, it’s about looking at the cumulative impact of various subtle risk factors,” Lanphear said in an interview. “Collectively, they may help explain such large variations in preterm birth around the world.”

Morgan said he’s witnessed substantial variation even across his state. Los Angeles, where he previously worked, has a lower rate of preterm births, 8.6 percent, than 220 miles north in Fresno, where the rate is 9.8 percent, according to the California Summit on Preterm Birth.

Even a small percentage change can mean thousands more babies born too soon. Preterm birth rates are also inconsistent within Fresno County — African American babies are born too early 12 percent of the time, for example, compared to 7.3 percent for non-Hispanic whites.

“We know that [toxics] are not equally distributed across the environment,” said Heather Burris, a neonatologist and expert in environmental exposures at Harvard Medical School. She has been studying racial and ethnic disparities in preterm births and finding hints that a mother’s – or even grandmother’s — environmental exposures likely account for some of the risk that a child arrives premature.

She, like Lanphear, lamented a general “under-appreciation” for the environment’s role. But much like research into the causes of autism, which had previously focused almost solely on genetics, toxic exposures may finally be coming into the spotlight.

“As the data have been getting better, we’ve been getting more broadly interested in environmental [toxics] and impacts on pregnancy,” said Dr. Edward McCabe, medical director of the March of Dimes. The organization has set two ambitious goals for the country’s preterm birth rate — 8.1 percent by 2020 and 5.5 percent by 2030 — by primarily targeting what he labeled “things we can control,” including family planning, avoiding alcohol while pregnant or trying to become pregnant and the use of progesterone and low-dose aspirin supplements.

He couldn’t point to any current investments by the March of Dimes into environmental factors, but said they have funded related research in the recent past.

Lanphear’s video comes as a public health disaster unfolds in Flint, Michigan. Among its many consequences, Lanphear said in an interview, the lead contaminating the city’s drinking water could trigger an uptick in preterm births. In fact, his video highlights a British study published in 2015, which found pregnant women with higher levels of lead in their blood were nearly twice as likely to give birth too soon.

Caroline Taylor, an environmental health expert at the University of Bristol, led that study. She suggested the need for “large-scale surveillance” to see what is happening to Flint’s pregnant women and children.

She also agreed in the broader need for research on the relationship between toxics and preterm birth.

“Lead is only one of a number of environmental exposures people come across during pregnancy,” Taylor said.

Flame retardants, phthalates and bisphenol-A (BPA) are among other toxics emerging as possible culprits in early births. Most recently, a study published in January – and partially funded by the March of Dimes — found exposure to high levels of particulate air pollution raised the risk of preterm births by 19 percent.

And just how these toxics might wreak their havoc on gestation is also under investigation. Tracey Woodruff, director of the University of California, San Francisco Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment, is eyeing potential impacts on the development of the placenta — the support system for the fetus. Flame retardants, phthalates, BPA and some pesticides are among chemicals that may mimic, and thereby disrupt, natural hormone messengers. And the implantation and development of the placenta, along with the rest of the architecture that connects mother to fetus, are guided by hormones.

She and other experts recommend pregnant women take steps to lower their risk of giving birth preterm, from choosing unprocessed and organic foods, when possible, to avoiding smoking, alcohol and the use of pesticides around their home. Yet many exposures remain out of an individual’s control.

Woodruff is also beginning to work with Morgan to sort out what environmental factors may be at play in Fresno.

She emphasized the potentially profound impact of exposures across an entire population. If the average child is born just a couple days earlier, explained Woodruff, that may mean a huge jump in the total number of premature babies — even if most children still spend adequate time in the womb.

In the video, Lanphear highlighted one example of how this statistical phenomenon should also inspire hope: After Scotland banned smoking in public places, non-smoking women experienced a 15 percent decline in preterm births and a 25 percent drop in very preterm births.

“We can prevent many babies from being born too soon,” he said. “Little things add up. Little things matter.”

EHN welcomes republication of our stories, but we require that publications include the author’s name and Environmental Health News at the top of the piece, along with a link back to EHN’s version.

Source: environmentalhealthnews.org