According to a report published on Wednesday which found that Antarctic ice will melt faster than previously thought, sea levels could rise 50 cm (20 inches) more this century than had been expected. Climate scientists at two U.S. universities said the most recent U.N. report on the effects of global warming had underestimated the rate at which the ice covering the continent would melt.

That report, issued in 2013, said the worst case of man-made climate change would mean a sea-level rise of between 52 and 98 cm by 2100. The new study suggests the real rise could be 1.5 meters (5 ft), posing an even greater threat to cities from New York to Shanghai.

Lead author Robert DeConto at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, said in a statement of the findings published in the journal Nature: “This could spell disaster for many low-lying cities,” adding “for example, Boston could see more than 1.5 meters of sea-level rise in the next 100 years.”

The study, partly based on sea level evidence in a natural warm period 125,000 years ago, said ice from Antarctica alone could cause between 64 cm and 114 cm of sea level rise by 2100 under the worst U.N. scenario for greenhouse gas emissions.

Working with David Pollard of Pennsylvania State University, DeConto calibrated this model using data on past sea level rises during warm periods 120,000 and 3 million years ago. Their model is the first to match what is thought to have happened during these periods.

They applied their model to several greenhouse gas emission scenarios and found that if emissions rapidly grow in future years, Antarctica alone could contribute well over 1 metre to global sea level by 2100. When this finding is combined with IPCC estimates, it suggests that we could be looking at a rise of over 2 metres by the end of the century, and 20 metres by 3500.

If countries meet the commitments they made as part of the Paris climate agreement, and continue to cut emissions after the agreement ends in 2030, then the world should be on track for a less severe rise in sea level. But DeConto’s model suggests that even this might not be enough to prevent rises that would devastate Miami and other low-lying cities within the lifetime of young people today.

Rapidly reducing global emissions could, in principle, avoid most Antarctic ice loss, says DeConto. In practice, we wouldn’t be able to replace fossil fuel infrastructure fast enough, even if the political will was there. “That’s not going to happen,” he says.

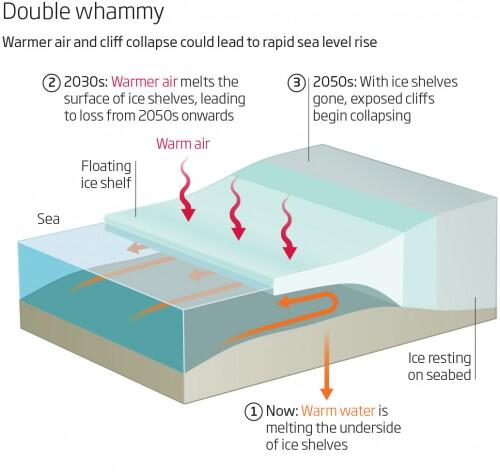

One of the factors that has was underestimated in the U.N. reports, which envisage most Antarctic ice remaining frozen, is a process known as “hydro fracturing” whereby pools of melt-water on ice shelves seep deep into the ice, refreeze and force vast chunks of ice to crack off. That could make ice on land in Antarctica slide faster into the sea.

Anders Levermann, an expert at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research who was not involved in the study, welcomed the findings as a spur to research hydro fracturing in Antarctica.

Several other studies have highlighted risks of rising seas. Former NASA scientist James Hansen suggested on March 22 that there could be “several meters” of sea level rise in the coming century. But Levermann dismissed Hansen’s findings.

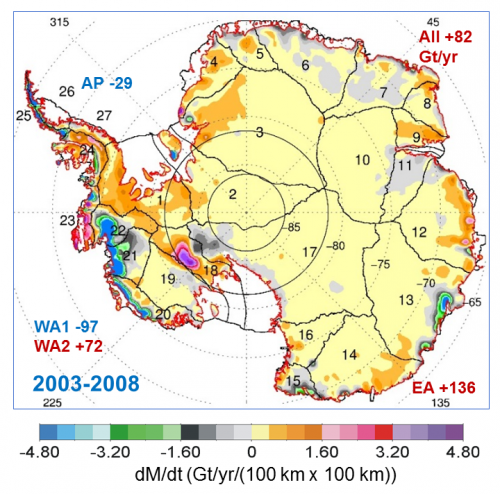

Map showing the rates of mass changes from ICESat 2003-2008 over Antarctica. Sums are for all of Antarctica: East Antarctica (EA, 2-17); interior West Antarctica (WA2, 1, 18, 19, and 23); coastal West Antarctica (WA1, 20-21); and the Antarctic Peninsula (24-27). A gigaton (Gt) corresponds to a billion metric tons, or 1.1 billion U.S. tons. Credits: Jay Zwally/ Journal of Glaciology

“It’s plain wrong,” he told Reuters of Hansen’s assumption that the rate of sea level rise could repeatedly double in coming decades. Wednesday’s study projected that Antarctica could contribute more than 13 meters of sea level rise by 2500 if the air and oceans keep warming.

NASA Study: Mass Gains of Antarctic Ice Sheet Greater than Losses

In October 2015, however, a NASA study said that an increase in Antarctic snow accumulation that began 10,000 years ago is currently adding enough ice to the continent to outweigh the increased losses from its thinning glaciers.

The research challenges the conclusions of other studies, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2013 report, which says that Antarctica is overall losing land ice.

According to the new analysis of satellite data, the Antarctic ice sheet showed a net gain of 112 billion tons of ice a year from 1992 to 2001. That net gain slowed to 82 billion tons of ice per year between 2003 and 2008.

“We’re essentially in agreement with other studies that show an increase in ice discharge in the Antarctic Peninsula and the Thwaites and Pine Island region of West Antarctica,” said Jay Zwally, a glaciologist with NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the study, which was published on Oct. 30 in the Journal of Glaciology. “Our main disagreement is for East Antarctica and the interior of West Antarctica – there, we see an ice gain that exceeds the losses in the other areas.” Zwally added that his team “measured small height changes over large areas, as well as the large changes observed over smaller areas.”

Scientists calculate how much the ice sheet is growing or shrinking from the changes in surface height that are measured by the satellite altimeters. In locations where the amount of new snowfall accumulating on an ice sheet is not equal to the ice flow downward and outward to the ocean, the surface height changes and the ice-sheet mass grows or shrinks.

But it might only take a few decades for Antarctica’s growth to reverse, according to Zwally. “If the losses of the Antarctic Peninsula and parts of West Antarctica continue to increase at the same rate they’ve been increasing for the last two decades, the losses will catch up with the long-term gain in East Antarctica in 20 or 30 years — I don’t think there will be enough snowfall increase to offset these losses.”

The study analyzed changes in the surface height of the Antarctic ice sheet measured by radar altimeters on two European Space Agency European Remote Sensing (ERS) satellites, spanning from 1992 to 2001, and by the laser altimeter on NASA’s Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) from 2003 to 2008.

Zwally said that while other scientists have assumed that the gains in elevation seen in East Antarctica are due to recent increases in snow accumulation, his team used meteorological data beginning in 1979 to show that the snowfall in East Antarctica actually decreased by 11 billion tons per year during both the ERS and ICESat periods. They also used information on snow accumulation for tens of thousands of years, derived by other scientists from ice cores, to conclude that East Antarctica has been thickening for a very long time.

“At the end of the last Ice Age, the air became warmer and carried more moisture across the continent, doubling the amount of snow dropped on the ice sheet,” Zwally said.

The extra snowfall that began 10,000 years ago has been slowly accumulating on the ice sheet and compacting into solid ice over millennia, thickening the ice in East Antarctica and the interior of West Antarctica by an average of 0.7 inches (1.7 centimeters) per year. This small thickening, sustained over thousands of years and spread over the vast expanse of these sectors of Antarctica, corresponds to a very large gain of ice – enough to outweigh the losses from fast-flowing glaciers in other parts of the continent and reduce global sea level rise.

Zwally’s team calculated that the mass gain from the thickening of East Antarctica remained steady from 1992 to 2008 at 200 billion tons per year, while the ice losses from the coastal regions of West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula increased by 65 billion tons per year.

“The good news is that Antarctica is not currently contributing to sea level rise, but is taking 0.23 millimeters per year away,” Zwally said. “But this is also bad news. If the 0.27 millimeters per year of sea level rise attributed to Antarctica in the IPCC report is not really coming from Antarctica, there must be some other contribution to sea level rise that is not accounted for.”

“The new study highlights the difficulties of measuring the small changes in ice height happening in East Antarctica,” said Ben Smith, a glaciologist with the University of Washington in Seattle who was not involved in Zwally’s study.

“Doing altimetry accurately for very large areas is extraordinarily difficult, and there are measurements of snow accumulation that need to be done independently to understand what’s happening in these places,” Smith said.

To help accurately measure changes in Antarctica, NASA is developing the successor to the ICESat mission, ICESat-2, which is scheduled to launch in 2018. “ICESat-2 will measure changes in the ice sheet within the thickness of a No. 2 pencil,” said Tom Neumann, a glaciologist at Goddard and deputy project scientist for ICESat-2. “It will contribute to solving the problem of Antarctica’s mass balance by providing a long-term record of elevation changes.”