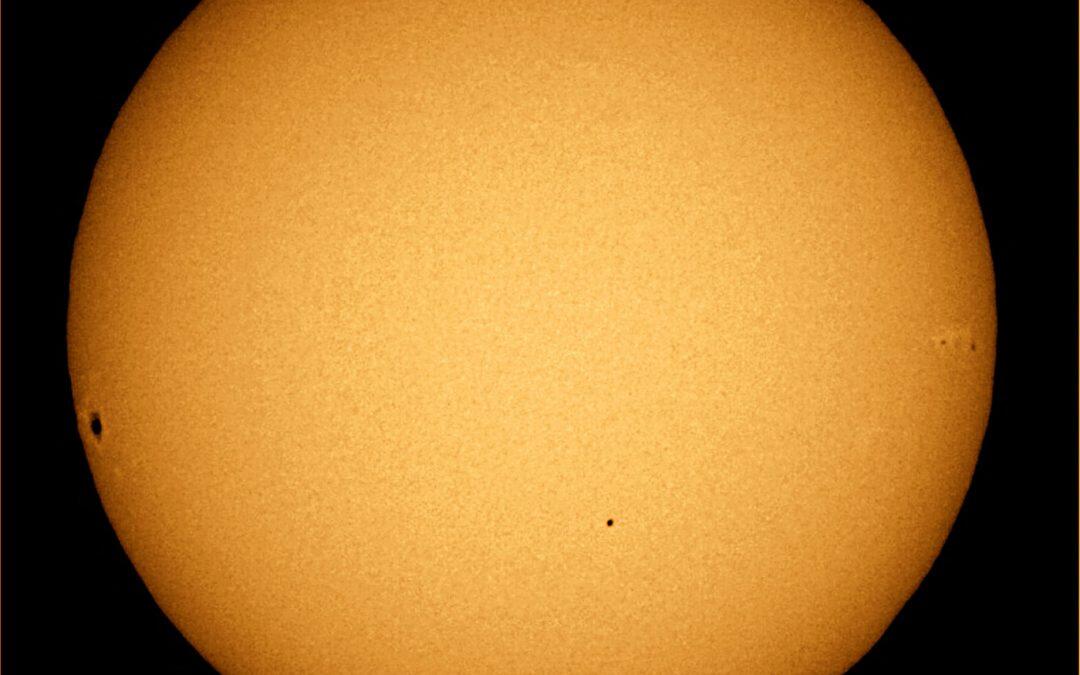

Next week, on Monday, May 9, skywatchers on Earth will be able to see Mercury make its way across the surface of the sun. The so-called transit of Mercury occurs only about 13 times every century, and the next one won’t take place until 2019.

The rare pass will be visible either partially or in full throughout most of the world. The event will not be visible in Japan and other parts of eastern Asia; Oceania and the nearby island nations; or Antarctica, according to a statement from the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). However, viewers in those areas can watch the event online.

Because Mercury and Venus are the only solar system planets that lie between the Earth and the sun, they are the only planets that transit the star as seen from Earth. Transits can be seen from other planets, too; in 2014, NASA’s Curiosity rover observed a transit of Mercury from Mars.

This map shows regions of the Earth where the 2016 Mercury transit will be visible. The transit will be visible in full or in part throughout most of the Earth, with the exception of eastern Asia, Australia and Antarctica. Credit: F. Espenak / eclipsewise.com.

Although both Mercury and Venus circle between the Earth and the sun on every orbit (with Mercury passing between the two bodies three times each Earth year), the three planets don’t sit in a flat orbit compared to one another. Only when Earth and a passing planet line up is the interior world visible to skywatchers as it crosses the sun.

Mercury’s transits currently take place in either early May or November. It is during those months that Earth’s orbital plane is intersected by Mercury’s, according to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. However, the orientation of the two orbital planes can change over long periods of time. In the past 700 years, two-thirds of the transits have occurred in November. In the fall, the planet appears as only 1/194 the size of the sun. Mercury looks larger in the sky in May, appearing to be about 1/158 the size of the background star.

The small apparent size of Mercury in the sky means that, unlike Venus, its transit cannot be seen using pinhole projectors. Instead, the best way for amateurs to view the event may involve projecting the image of the sun using binoculars or a telescope.

WARNING: Do NOT attempt to observe the sun without appropriate eye protection. Looking directly at the sun can cause permanent eye damage or blindness.

The transit stages

Mercury’s transit can be broken into five stages. These stages will occur at slightly different times based on the observer’s location on Earth, but the times should not vary by more than 2 minutes, according to an article from the Observers Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.

The first stage, called contact I, begins precisely at 1112:19 GMT (7:12:19 a.m. EDT), when the edge of the planet’s disc kisses the sun’s edge in the sky. Soon after, the planet will appear to make a small notch in the sun. The notch will grow larger until contact II occurs at 1115:31 GMT (7:15:31 a.m. EDT), when the entire disc lies within the sun while both outer edges touch. Over the course of several hours, the planet will cross the sun, reaching the star’s center at 1457:26 GMT (10:57:26 a.m. EDT). At contact IV (1839:14 GMT/2:39:14 p.m. EDT), the outer edge of the planet’s disc will touch the outer edge of the sun, and by contact V (1842:26 GMT/2:42:26 p.m. EDT), the planet will have completed its cross of the sun, and its inner edge will have just touched the star’s outer edge.

Although Mercury is more challenging to see than Venus, the small planet made the first observed transit. French astronomer Pierre Gassendi relied on predictions made by Johannes Kepler to make the first observation of a planet transit when he observed Mercury passing in front of the sun in 1631, according to the RAS. The first Venus transit wasn’t recorded until 1639.

Capt. James Cook’s historic voyage on the HMS Endeavour is well known for observations of the June 3, 1769, Venus transit, according to David Rothery, a professor of planetary geosciences at the Open University in the United Kingdom. Both Cook and the expedition’s astronomer, Charles Green, observed a transit of Mercury on Nov. 9 of the same year from New Zealand. Green was the first to note that the crisp outline of Mercury suggested that it has little or no atmosphere. Rothery wrote about the upcoming Mercury transit in a presentation brief for the 2015 Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference.

Many observatories and amateur astronomy groups will have events highlighting the pass; check your local societies for more information. The Slooh Community Observatory will host a free webcast of the event that will “[bring] together dozens of feed partners from countries across the globe, giving viewers a once-in-a-lifetime look at the small planet’s journey.” You can follow the science fun on Twitter with the hashtag #MercuryTransit2016.

Source: Space.com, NASA