The yellow-brown haze obscuring Colorado Front Range skies has wafted into national parks and wilderness, hurting habitat and reducing how far people can see by up to 60 miles — a problem federal authorities tried to tackle Wednesday in Denver.

But an Obama administration proposal to tighten the nation’s regional haze rule faces turbulence over details such as how fast states must ramp up their plans to meet a 2064 goal of restoring pristine natural clarity. Under the Environmental Protection Agency proposal, all states would be obligated to control air pollution that spreads beyond state boundaries.

“Our protected natural areas are some of the few places where I thought I could take my daughter and not have to worry about pollution,” Denver mother Jen Clanahan, a member of Colorado Moms Know Best, testified at an EPA hearing.

“If I can’t take her to our national parks to escape, I’m not sure where to go. It leaves me feeling like we can’t escape the pollution we’re breathing in all the time, like I can’t get my daughter away from it. As a parent, you want to protect your child and to feel like you can’t is a frustrating and scary feeling. … For the sake of my daughter, of all of our kids and their kids, please implement the changes that have been proposed to make the Regional Haze Rule stronger.”

Industry officials insist existing coal-fired power plants and fossil fuel facilities must keep operating.

States want to play the lead role in measuring visibility and deciding where views are impaired. Colorado also is seeking flexibility to conduct prescribed burns in forests that temporarily reduce visibility but improve forest health.

Environmental groups demand tougher state cleanup plans by 2018 as initially required, not 2021 as proposed.

EPA spokeswoman Enesta Jones said proposed rule changes “will build on the progress states and the EPA have made” to improve visibility in parks and wilderness. “The updates will ensure that haze-forming pollution continues continues to be reduced, while providing states and industry the time, tools and flexibility they need to meet Clean Air Act requirements.”

Colorado health officials monitor particulate air pollution in national parks and visibility distances, working with federal land managers. A first state five-year plan helped cut haze significantly in some parks.

State officials on Wednesday objected to haze rule tweaks that would give federal land managers lead roles in measuring visibility and declaring violations.

Eventual implementation of the national Clean Power Plan to phase out coal-burning power plants will help improve visibility in parks and wilderness, said Will Allison, director of Colorado’s air pollution control division. He noted that emissions from a power plant in Nebraska blow back east-west into the Rocky Mountain and Great Sand Dunes national parks.

“Now it will be more challenging, as we move forward, to look at smaller sources that collectively contribute to visibility impairment,” Allison said. “We don’t want to be penalized for intelligent, well-designed prescribed fire programs.”

A haze rule made in 1999 under the Clean Air Act was supposed to put the nation on track to restore natural air conditions in parks and wilderness, removing the haze that is made up of sulfur dioxide, ozone, mercury, nitrogen oxides and other toxic emissions.

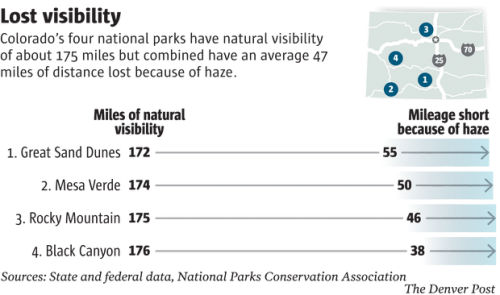

But even with the rule, visibility still is impaired, state and federal data show. In Colorado, the average distance people can see in Rocky Mountain National Park is reduced by 46 miles compared with natural conditions — the amount that is missing because of haze. At the Great Sand Dunes, visibility is reduced by 55 miles. The distance people can see is reduced by 38 miles in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison and 50 miles at Mesa Verde.

Air quality in Colorado wilderness areas (Weminuche, La Garita, Mount Zirkel, Rawah, Eagles Nest, Flat Tops, Maroon Bells-Snowmass, West Elk) also has deteriorated, data show.

On Wednesday, EPA officials took action under the existing haze rule

against two power plants in Utah — PacificCorp’s Hunter and Huntington

plants — contributors to haze in Utah’s Canyonlands, Arches and other parks and wilderness areas.

While the ability to see stars and mountains is impaired compared with pre-industrial conditions, data show that visibility in the Colorado parks improved during the past decade by, on average, 14 miles.

“We are gaining a few miles. We’re seeing improvement. But we have a long way to go,” said Ulla Reeves, clean air campaign manager for the National Parks Conservation Association. “Haze is air pollution. And air pollution does not belong in our national parks.”

An expanded role for federal land managers identifying problems “is a good thing,” Reeves said. “The federal land managers know their parks and wilderness areas — and air conditions — better than anybody else,” Reeves said.

Reaching the goal of having natural air in parks by 2064 likely won’t happen without tougher measures.

But Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association policy analyst Lyle Witham, supporting the extended 2021 deadline for states, emphasized a requirement that existing power plants must be able to keep running through their “remaining useful lives.” Once this is factored into the EPA’s effort, it could still be possible to restore pristine air in parks by 2064, depending on how “natural” conditions are defined in relation to wildfire, Witham said.

“We’re getting there. It will happen over time.”

Source: The Denver Post

Author: Bruce Finley