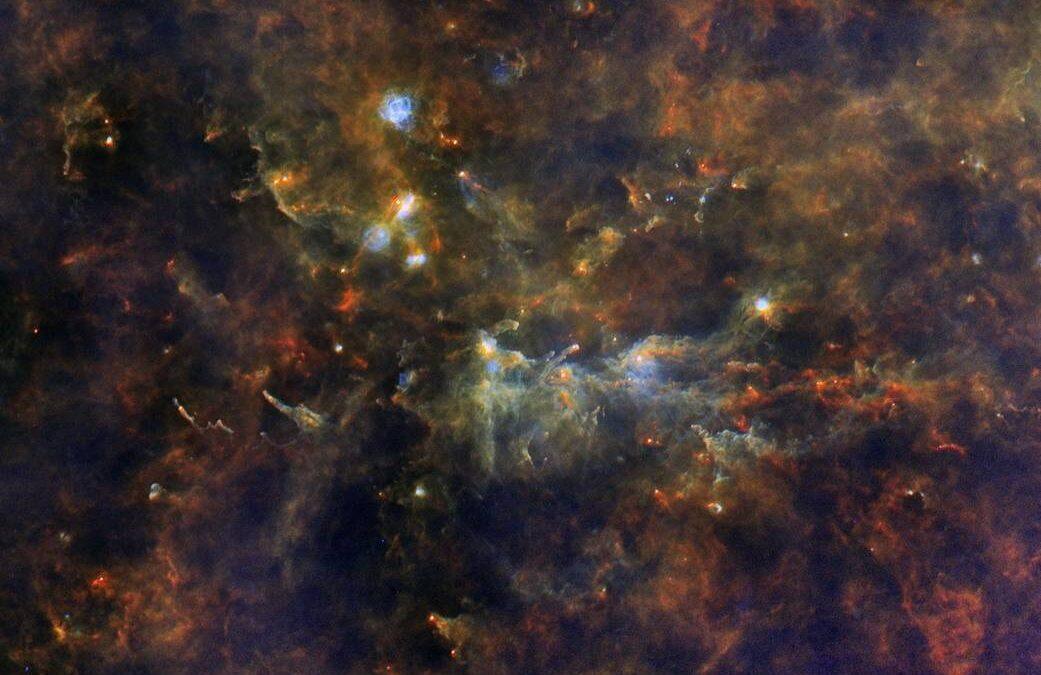

New stars are the lifeblood of our galaxy, and there is enough material revealed by this Herschel infrared image to build stars for millions of years to come.

Situated 8,000 light-years away in the constellation Vulpecula — Latin for “little fox” — the region in the image is known as Vulpecula OB1. It is a “stellar association” in which a batch of truly giant “OB” stars is being born. O and B stars are the largest stars that can form.

The giant stars at the heart of Vulpecula OB1 are some of the biggest in the galaxy. Containing dozens of times the mass of the sun, they have short lives, astronomically speaking, because they burn their fuel so quickly. At an estimated age of 2 million years, they are already well through their lifespans. When their fuel runs out, they will collapse and explode as supernovas. The shock this will send through the surrounding cloud will trigger the birth of even more stars, and the cycle will begin again.

O stars are at least 16 times more massive than the sun, and could be well over 100 times as massive. They are anywhere from 30,000 to 1 million times brighter than the sun, but they only live up to a few million years before exploding. B-stars are between two and 16 times as massive as the sun. They can range from 25 to 30,000 times brighter than the sun.

OB associations are regions with collections of O and B stars. Since OB stars have such short lives, finding them in large numbers indicates the region must be a strong site of ongoing star formation, which will include many more smaller stars that will survive far longer.

The vast quantities of ultraviolet light and other radiation emitted by these stars is compressing the surrounding cloud, causing nearby regions of dust and gas to begin the collapse into more new stars. In time, this process will “eat” its way through the cloud, transforming some of the raw material into shining new stars.

The image was obtained as part of Herschel’s Hi-GAL key-project. This used the infrared space observatory’s instruments to image the entire galactic plane in five different infrared wavelengths.

These wavelengths reveal cold material, most of it between -220º C and -260º C. None of it can be seen in ordinary optical wavelengths, but this infrared view shows astronomers a surprising amount of structure in the cloud’s interior.

The surprise is that the Hi-GAL survey has revealed a spider’s web of filaments that stretches across the star-forming regions of our galaxy. Part of this vast network can be seen in this image as a filigree of red and orange threads.

In visual wavelengths, the OB association is linked to a star cluster catalogued as NGC 6823. It was discovered by William Herschel in 1785 and contains 50 to 100 stars. A nebula emitting visible light, catalogued as NGC 6820, is also part of this multi-faceted star-forming region.

Herschel is a European Space Agency mission, with science instruments provided by consortia of European institutes and with important participation by NASA. While the observatory stopped making science observations in April 2013, after running out of liquid coolant as expected, scientists continue to analyze its data. NASA’s Herschel Project Office is based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. JPL contributed mission-enabling technology for two of Herschel’s three science instruments. The NASA Herschel Science Center, part of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, supports the U.S. astronomical community. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.

Source: NASA