Europe will push ahead with its plan to put a UK-assembled robotic rover on the surface of Mars in 2021.

Research ministers meeting in Lucerne, Switzerland, have agreed to stump up the outstanding €436m euros needed to take the project through to completion.

The mission is late and is costing far more than originally envisaged, prompting fears that European Space Agency member states might abandon it.

But the ministers have emphatically reaffirmed their commitment to it.

They have also said that European participation in the International Space Station (ISS) should run until at least 2024, bringing Esa into line with its partners on the orbiting laboratory – the US, Russia, Japan and Canada.

This will open new opportunities for European astronauts to visit the station, and it was announced here that Italian Luca Parmitano has been proposed to take up a tour in 2019.

The Ministerial Council was convened to set the policies, programmes and funding for Esa over the next three to five years.

Officials at the agency had put a menu before member state delegations valued at some €11bn (£9.5bn; $12bn), covering all manner of activities ranging from rockets and Earth observation to big data management and satellite navigation.

At the end of one and a half days of deliberations, the 22 governments agreed to fund €10.3bn.

“This is a big amount of money that really allows us to go forward,” said Prof Jan Woerner, the director general of Esa.

“We need inspiration for the future. Inspiration is a driver, and from inspiration and fascination come motivation. And for me, it’s very clear we are responsible for the motivation of the next generation to create the future.”

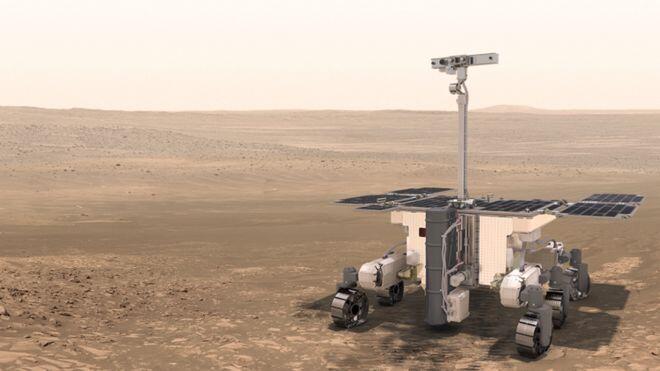

The rover is the second part in a two-step programme known as ExoMars, which is being run jointly with the Russians to explore the possibility of life on the Red Planet.

The first part has just seen a satellite arrive at Mars to investigate trace gases in the atmosphere that may be coming from microbes somewhere on the world.

In the second phase, a robotic rover would follow up these studies by drilling below Mars’ dusty surface to try to detect the organisms directly.

But repeated delays in the vehicle’s development have increased costs and undermined confidence in the whole endeavour.

Ministers were asked here to reassert their faith in the mission and close the sizeable financial shortfall that has built up.

This they did, committing €339m to cover industry costs on the rover and its associated hardware (Esa is finding another €97m internally).

Italy and the UK, which are the lead nations on ExoMars, offered the most – €171m and €82m respectively.

“Completion of ExoMars was probably the most challenging of our discussions because of the size of the additional resources that have been put on the table,” said Prof Roberto Battiston, the president of the Italian space agency (ASI).

“But this was justified by the detailed analysis presented by Esa. We are covering about 45% of the total cost of the mission, which makes us the country that is particularly sensitive to the cost of it.”

Dr David Parker, Esa’s director of human spaceflight and robotic exploration, said member states stepped up because they continued to view the rover’s science as being compelling.

“Nobody else is doing the science that is planned for ExoMars, drilling below the surface of the planet for the first time, below the soil that is irradiated, with a suite of instruments that is actually directly looking for signs of past or present life,” he told BBC News.

Britain came to the meeting looking to invest heavily in those areas that feed back into its industrial interests.

This meant making big commitments in satellite telecommunications, in commercial services that involve space data and applications, in Earth observation satellites, and in navigation.

In telecoms and navigation, the UK is the number one nation in Esa following this ministerial. That was to be expected. But Britain also put the most into the environmental sciences, which means it now leads Esa in Earth observation as well. Ahead of Germany. That is a first.

“It’s a story about recognising where the new market opportunities are,” said Dr Alice Bunn, the UK Space Agency’s director of policy.

“We’ve seen it in telecommunications, but we’re seeing it now also in navigation where there is potentially a €30bn market out there in new types of services. And hot on the heels of navigation are opportunities in Earth observation, and we want to position ourselves on the front foot for that.”

And to underline the €1.4bn total commitment (over five years) that the UK gave to Esa in Lucerne, science minister Jo Johnson signed an agreement with Mr Woerner to expand activities at Esa’s European Centre for Space Applications and Telecommunications (Ecsat), based in Harwell, Oxfordshire.