Vietnam’s population is becoming more environmentally conscious as industrialization has come at a cost to nature.

Vietnamese people are unhappy with solutions given to environmental disputes with businesses, a recent study has found.

Local authorities, who act as mediators in these disputes, often find themselves in “tough” situations trying to balance economic and environmental interests, said a joint study by the United Nations Development Programme and the National Economics University (NEU).

The study, which looked into 17 biggest environmental disputes that occured across Vietnam in the past six years, highlights the need to better understand environmental disputes and their socio-economic and political implications, said UNDP country director in Vietnam, Caitlin Wiesen.

In all 17 disputes considered, affected locals found the solutions unsatisfactory.

The problem, according to Professor Tran Tho Dat of the NEU, is that most prior research focused mainly on levels of pollution, without due consideration of socio-economic and political implications. A one-sided focus on the harm caused by pollution can underestimate the sense of injustice that animates and amplifies environmental disputes.

Vietnam’s population is becoming more environmentally conscious as an economic boom brought by industrialization has resulted in air pollution in big cities, toxic spills and environmental degradation.

The 2016 Viet Nam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) points out that environmental concerns are the second most urgent matter that Vietnamese citizens want their government to address, just after poverty and hunger.

As many as 77 percent of PAPI respondents said Vietnam should prioritize environmental protection over economic growth at all costs.

In fact, both natural and manmade environmental problems will continue to consume about 0.6 percent of Vietnam’s annual GDP from now until 2020, according to a 2016 study by Vietnam’s National Center for Socio-Economic Information and Forecast.

Meanwhile, Vietnam is aiming for high GDP growth of 6.7 percent for 2018, led by foreign invested firms, export oriented manufacturing, natural resource extraction and mass tourism.

Foreign invested firms in particular have often been linked to environmental disputes. Out of 50 major toxic waste scandals recorded in 2016 by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, 60 percent were caused by foreign invested firms, including the notorious mass fish deaths that made international headlines.

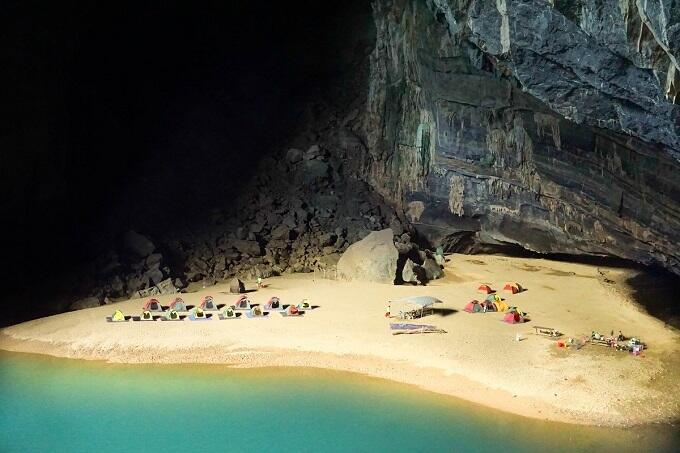

More recently, the ongoing controversy surrounding the prospects of building a cable car into Swallow (En) Cave, a feeder to world’s largest cave Son Doong in Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, is an example of how environmental disputes do not necessarily start after a disaster happens. The case reflects a stark conflict of interests between environmentalists who see it as a potential ecological disaster and Quang Binh provincial authorities who see it as a golden tourism opportunity.

Last year, the controversy intensified after Tran Cong Thuan, the deputy chief of Quang Binh’s Communist Party unit, claimed “a majority of the public agree with the plan and believe that it will help local tourism,” without providing details on who or how many people were surveyed.

This is despite the fact that more than 143,000 have signed an online petition against the project.

This is why Wiesen of the UNDP stresses that communities need to be consulted before governments take actions that affect the environment. Individuals need to have access to information and participate in the decision making process regarding environmental matters that affect them and given access to courts to settle disputes.

Even when it comes to technical matters like measuring levels of pollution, inconsistencies in the law and implementation make matters worse, according to legal environmental expert Nguyen Hoang Phuong.

“Most environmental disputes depend on an evidence-based system, which is very weak,” said Phuong. “In the case of the Nicotex factory in Thanh Hoa, for instance, wastewater samples collected by residents and authorities were tested at different labs and collected using different methods.”

“If we continue to apply such mechanisms, issues concerning environmental justice cannot be solved.”

Source: http://bit.ly/2DRLVSe