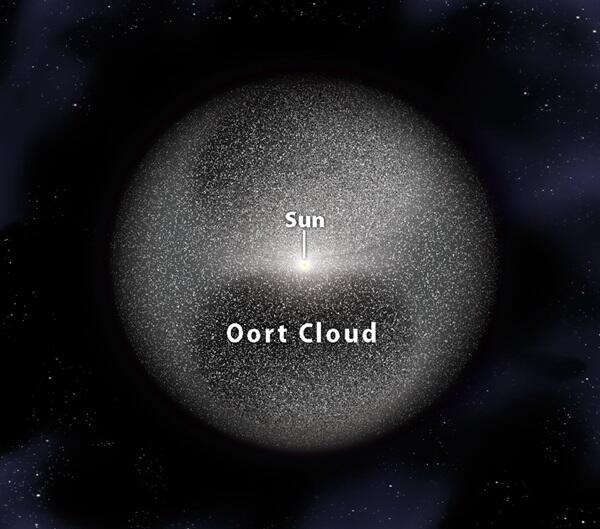

About 2,000 to 5,000 astronomical units (AU; where 1 AU is the average distance between Earth and the Sun) from the Sun lies the beginning of the Oort Cloud. For context, the Voyager spacecrafts — the human-made objects that have traveled farthest from our Sun — will cross this inner edge of our solar system in about 300 years. From there, the Oort Cloud stretches to about 10,000 to 100,000 AU (0.16 to 1.6 light-years), according to NASA. But keep in mind this outer boundary is pretty nebulous, so there is no hard line where the Oort Cloud ends.

All this is to say that it isn’t clear how close the Oort Cloud actually gets to the Alpha Centauri system, which is about 4.3 light-years away. Even if the Oort Cloud does stretch halfway to the other system, scientists aren’t sure whether it has its own Oort Cloud.

Despite searching, astronomers have seen no direct evidence of extrasolar Oort Clouds (and they’ve been looking since 1991). Because these clouds would be so far from their stars and aren’t very dense, spotting them would be exceedingly difficult.

Our Oort Cloud is influenced by other systems. The Oort Cloud is outside of the Sun’s heliosphere — the protective magnetic bubble that separates our solar system from interstellar space. The solar system also sits closer to the edge of the Milky Way than the center. This means that one side of the solar system feels a stronger gravitational pull than the other. This gradually jostles the Oort Cloud, sometimes sending long-period comets into the inner solar system. Passing stars and molecular clouds can have similar effects. Likewise, as our nearest celestial neighbor, the Alpha Centauri system likely has some effect, albeit a small one, even at its distance. But Alpha Centauri is actually approaching the Sun. In about 30,000 years, the trio of stars will come within about 2.9 light-years of our star, at which point its influence will be much stronger.