- by Lucy Jones |

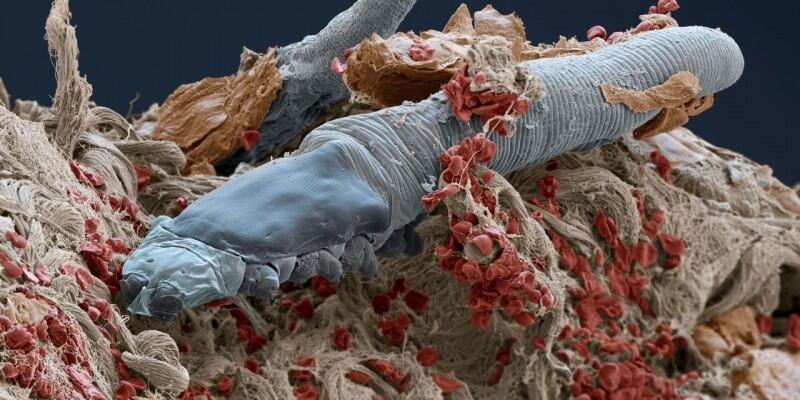

You almost certainly have animals living on your face. You can’t see them, but they’re there. They are microscopic mites, eight-legged creatures rather like spiders. Almost every human being has them. They spend their entire lives on our faces, where they eat, mate and finally die. Before you start buying extra-strong facewash, you should know that these microscopic lodgers probably aren’t a serious problem. They may well be almost entirely harmless. What’s more, because they are so common they could help reveal our history in unparalleled detail. There are two species of mite that live on your face: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. They are arthropods, the group that includes jointed-legged animals such as insects and crabs. Being mites, their closest relatives are spiders and ticks. Demodex mites have eight short and stubby legs near their heads. Their bodies are elongated, almost worm-like. Under a microscope, they look as though they’re swimming through oil, neither very far, nor very fast. The two species live in slightly different places. D. folliculorumresides in pores and hair follicles, while D. brevis prefers to settle deeper, in your oily sebaceous glands. Compared with other parts of your body, your face has larger pores and more numerous sebaceous glands, which may explain why the mites tend to live there. But they have also been found elsewhere, including the genital area and on breasts. Scientists have known that humans carry face mites for a long time. D. folliculorum was spotted in human earwax in France in 1842. In 2014, it became clear just how ubiquitous they are. Megan Thoemmes of North Carolina State University in Raleigh and her colleagues found, as had previous studies, that about 14% of people had visible mites. But they also found Demodex DNA on every single face they tested. That suggests we all have them, and probably in quite large numbers. “It’s hard to speculate or quantify but a low population would be maybe in the hundreds,” says Thoemmes. “A high mite population would be thousands.” Put another way, you may have around two mites per eyelash. The populations may well vary from person to person, so you might have many more than your neighbour or far fewer. You may also have more mites on one side of your face than the other. Yet it’s not clear what the mites are getting from us. For starters, we’re not sure what they eat. “Some people think they eat the bacteria that are associated with the skin,” says Thoemmes. “Some think they eat the dead skin cells. Some think they’re eating the oil from the sebaceous gland.” Thoemmes and her colleagues are currently looking at the microorganisms that live in the mites’ guts. That could help determine their diet. We also don’t know much about how they reproduce. Other species of mite get up to all sorts of things, from incest and sexual cannibalism to matricide and fratricide. But so far it seemsDemodex are a little less extreme. “They’ve never been known to eat one another,” says Thoemmes. “It appears that they come out at night to mate and then go back to their pores.” The only thing we know about is their eggs. Female Demodex mites lay their eggs around the rim of the pore they are living in. But they probably don’t lay many. “Their eggs are quite large, a third to a half the size of their body, which would be very metabolically demanding,” says Thoemmes. “They’re so large they’re probably laying one at a time, as I can’t imagine that more than one can fit in their bodies based on the size.” Speaking of objects that Demodex need to push out of their bodies, these mites also don’t have anuses. They still need to poo, so it’s been said that they ‘explode’ with waste at the end of their lives. However, that’s “a bit of an over-exaggeration”, says Thoemmes. They do save it all up until death, though. When a Demodex dies, its body dries out and all the built-up waste degrades on your face. “It’s not an exploding action necessarily, but it’s true that all their waste builds up over time and then there’s one large flush of bacteria,” says Thoemmes. “It’s not just coming in discrete units over time, it’s a lot built up that comes out.” That may sound terrible. But surprisingly, it looks as though these mites are not harmful. “I would think that they’re not harming us in a way that’s detectable,” says Thoemmes. “If we were having a strong negative response to their presence, we’d be seeing that in a greater number of people.” The one thing they have been linked to is a skin problem calledrosacea. This mainly affects people’s faces, and begins with flushing before sometimes progressing to permanent redness, spots, and sensations of burning or stinting. Studies have found that people suffering from rosacea tend to have more Demodex mites. Instead of 1 or 2 per square centimetre of skin, the number rises to 10 to 20. But that doesn’t mean the mites cause the problem. “The mites are involved in rosacea, but they’re not causing it, “says Kevin Kavanagh of Maynooth University in Ireland. In a study published in 2012, he concluded that the root cause was changes in people’s skin. Our skin gradually changes over the years, for instance due to ageing or exposure to the weather. This alters the sebum, an oily substance produced by the sebaceous glands that helps keep our skin moist. Demodex are thought to eat the sebum, and the change in its makeup may cause a population boom. “This causes irritation in the face, just because there are so many mites around,” says Kavanagh. There also seems to be a link between rosacea symptoms and the big flush of bacteria released when a mite dies. “When the mites die, they release their internal contents,” says Kavanagh. “This contains a lot of bacteria and toxins that cause irritation and inflammation.” There may also be a link with the immune system, which normally protects us against infections. Thoemmes says the mites have been found to be particularly abundant on people with immune deficiencies, such as AIDS or cancer. It’s still not clear what sort of relationship we have with ourDemodex mites. We can be sure they are not parasites, which take things from us and cause harm in the process. The relationship might instead be commensal, meaning that they do take something from us but not in a way that normally causes harm. For most people, most of the time, they’re harmless. They may even be beneficial. For instance, they may clear dead skin off our faces or eat harmful skin bacteria. But suppose you really wanted to get rid of them. Could you? Although there are therapies that kill Demodex mites, we can’t get rid of them forever. They rebound after about six weeks, says Kavanagh. “We pick them up from people who we are in contact with. We pick them up from sheets, pillows, towels. There’s good evidence that we transmit them between each other.” It looks as if there is something special on our faces that they need. Even if you kill them off, you’re going to get them again, because they’re everywhere and they want to be on your face. In line with that we may pick upDemodex very early in life. “Demodex mites have been found in mammary tissue,” says Thoemmes. As a result, she suspects they travel from mother to baby, perhaps through breast-feeding or even at birth. We may then pick up a few more from the people we know as we grow older. Thoemmes’s study found more mite activity on adults over 18 than on 18-year-olds. Thoemmes speculates it might be “since we evolved from our hominid ancestors”. That would mean we’ve been carrying these animals for 20,000 years. We might have picked them up from other animals. D. brevis is particularly similar to a species that lives on dogs. Humans have long had a close relationship with domestic dogs, and with their wild relatives, wolves. Thoemmes suggests our ancestors “lived closely with them, for hunting purposes or that kind of thing”, and picked up the mites as a result. As well as our relationships with animals, the mites could reveal a lot about our relationships with each other. Their genes contain clues to our history. When Thoemmes looked at the mites’ DNA, she found that mites collected from Chinese populations were distinctly different from those collected from North and South American populations. Because these differences exist, studying the mites could tell us how our distant ancestors migrated around the planet, and reveal which modern populations are most closely related. “We might be able to figure out human associations… we weren’t able to figure out or see before,” says Thoemmes. She is particularly interested in finding out about the colonisation of Central and South America. “There’s been a lot of speculation as to which populations of humans colonised Brazil and inter-bred,” she says. Demodex could also allow us to peer much further back in time, and investigate how we evolved. If they’ve lived with us for so long, it is possible our immune systems have changed as a result. These little mites may have helped shape how we respond to disease. “They most certainly have an effect on us, as we do on them,” says Thoemmes. “We could be having immune responses to them, which could have been having an effect on our health and immune systems.” For now, this is all speculation. But even if none of these ideas pay off, the story of Demodex is a reminder that we humans are home to a multitude of species. Some, such as head lice and fleas, hop aboard occasionally, or only live on certain populations. Others, like Demodex and the microorganisms in our guts, are with all of us throughout our lives. Our bodies are seething with microorganisms: they make up 90% of our cells. There is a simple lesson here. You are not just you: you are a walking, talking community, an entire ecosystem held within one body. BBC