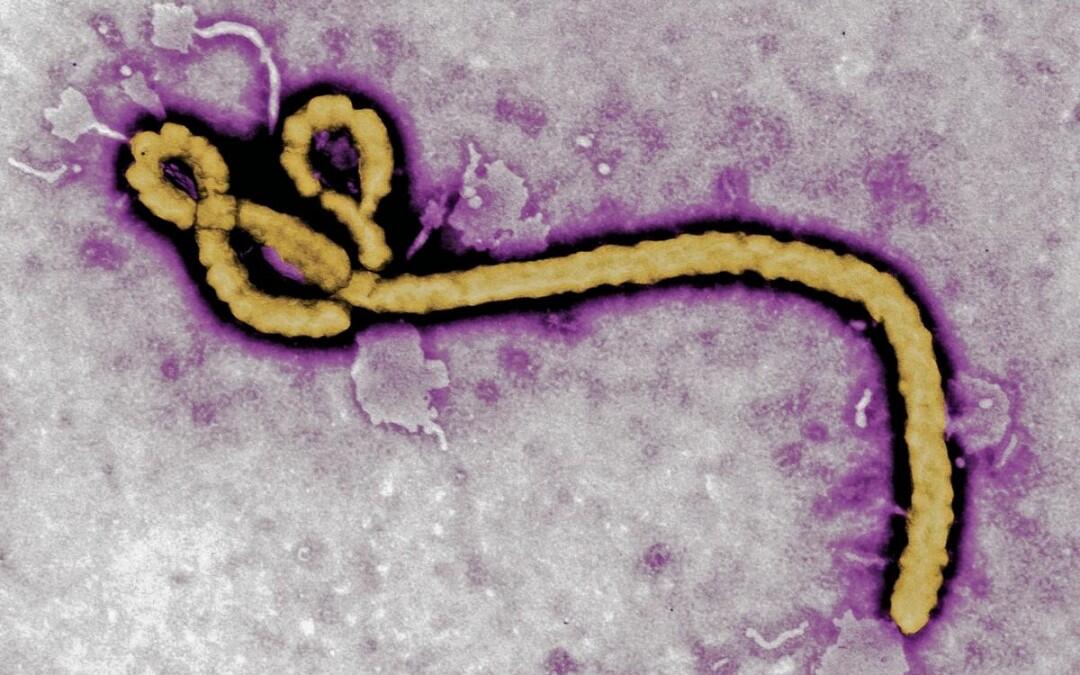

Prepared by – Suzanne Abou Said Daou | Only two months after being officially declared Ebola-free, the Ebola virus worry emerged when more cases of the deadly disease struck Liberia, and without any complacency from health officials, but there’s a deep need for effective preventative measures. Many vaccines are in the development phase with hopes that we could have one by the end of the year. But no licensed vaccines are available now, but now an inhalable vaccine has been shown to provide non-human primates with protection. Not only is this type of vaccine a first for Ebola, but the delivery method could prove extremely useful in remote areas of developing nations. The study to document the findings, was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation in the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston. In the new study, Bukreyev and colleagues administered the inhaled vaccine to six rhesus macaque monkeys. A month later, the team injected the monkeys with a dose of Ebola virus that was 1,000 times the level that would normally be deadly. None of the monkeys died or developed severe cases Ebola, although a few developed mild depression. The new vaccine is made from a mild, very common respiratory virus, called human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) that has been engineered to include genes from the Ebola virus that encode the proteins of the virus’s outer coat. The researchers found that the engineered virus infiltrated monkey’s respiratory tracts, and replicated there, triggering the cells to produce many copies of the Ebola virus’s coat. The immune system, in turn, recognized that outer coat as foreign, and activated a response. And following the observations that an individual can become infected if the virus comes into contact with the mucus-lined membranes of the respiratory tract, indicating that these protective barriers to the delicate airways could serve as an entry point for the pathogen, the idea of the inhalable vaccine was born. Furthermore aerosolized delivery has never before been tested for an Ebola vaccine or any other viral hemorrhagic fever vaccine. The new vaccine would be an improvement over other vaccines not only because it could be delivered by people other than medical professionals. Postdoctoral fellow Michelle Meyer co-author of the study commented that “A needle-free, inhalable vaccine against Ebola presents certain advantages, and Immunization will not require trained medical personnel”. “This study demonstrates successful aerosol vaccination against a viral hemorrhagic fever for the first time”, said senior author Alex Bukreyev, a professor at UTMB. “A single-dose aerosol vaccine would enable both prevention and containment of Ebola infections, in a natural outbreak setting where healthcare infrastructure is lacking or during bioterrorism and biological warfare scenarios”, Mr Bukreyev said. While further studies are needed to confirm that the vaccine is both safe and effective, it may likely take at least three years before the vaccine be used in the field, one can’t look the other way, when faced with the figures, where Ebola epidemic that lasted 18 months in west Africa has sickened more than 27,000 and left more than 15,000 dead, mostly in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, according to the World Health Organization.